The region’s suburbs may be entering a new phase of competitive growth

Suburban real estate development was a commanding force that helped propel the New Jersey economy to extraordinary heights for more than one-half century following World War II. During this period, it helped define and shape the state’s core economic competence and provided sustained regional economic and demographic leadership. But the suburban arena seemingly lost its mojo as the Great 2007-2009 Recession commenced and then, in the post-recession years, began to struggle, sometimes mightily. One metric of this change was the dramatic slowdown in suburban population growth in the post-2010 years. The once unique capabilities and proficiencies of New Jersey, often labeled the most suburban of states, seemingly were under assault.

But our latest Rutgers Regional Report, “The ‘Burbs’ Bounce Back,” suggests that New Jersey’s (and the broader region’s) suburbs may be entering a new phase of competitive growth following the extended malaise that characterized them for most of the post-recession period.[1] The report focuses on the changing geographic population growth patterns of the 35-county, four-state metropolitan region centered on New York City. It documents that, in a sharp departure from long-term twentieth century trends, the overall population growth in the region’s 27 suburban counties (suburban ring) between 2010 and 2016 had lagged significantly behind the burgeoning eight-county regional core (New York City’s five boroughs plus New Jersey’s Essex, Hudson and Union counties). However, new census population estimates for 2017 show the suburban counties again dominating regional growth. This reversal appears to be consistent with what has been happening nationally: “Newly released census data for the first seven years of this decade signal a resumption of the population dispersal that was put ‘on hold’ for a good part of the post-Great Recession period. The Census Bureau’s annual county and metropolitan area estimates through 2017…leave little doubt that suburbanization is on the rise, after a decided lull in the first part of the decade.”[2] Is New Jersey now closely following the changing national dynamic?

Historical Background

A brief historical perspective on our current analysis is warranted. Four years ago (2014), Professor Joseph J. Seneca and I produced a Rutgers Regional Report entitled “The Receding Metropolitan Perimeter” (the 37th report in series dating back more than 25 years). Based on 2010 to 2013 census population estimates, it suggested that transformative and disruptive demographic shifts were starting to unfold: the unbridled suburbanization/urban decline of the region in the twentieth century was being reversed and supplanted by the urban resurgence/suburban malaise of the twenty-first century. Moreover, broad suburban lag was also being accompanied by outright population decline in the outer perimeter counties of the region.[3]

Being conservative in our assertions, we were careful to note that “Three years do not a trend make.” However, subsequent data (2014 through 2016) strongly confirmed this “new” trend’s continuation and seeming durability. But even with six years of data (2010-2016) we now update that same caveat: “Six years do not a trend make.” Because the most recent census estimates (2017) reveal a reversal of this course: suburban population growth in the region, at least for the latest year of data, has again surpassed that of the urban core. While we certainly acknowledge that such short-term data may not herald a new sustainable dynamic, uncertainties and questions abound about future real estate development trends in the region.

What do the Data Say?

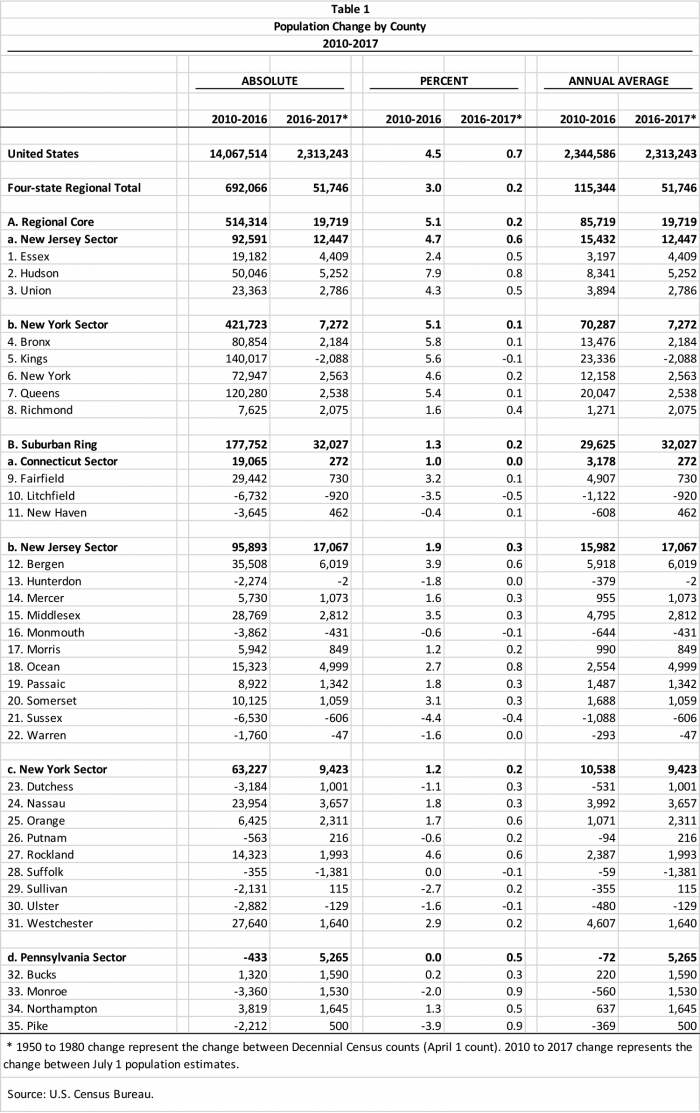

Here’s what the most recent post-2010 data tell us. During the 2010-2016 period, in what had been a sharp departure from historical twentieth century development patterns, the broad four-state metropolitan region centered on New York City had a total population growth of 692,066 people (Table 1).

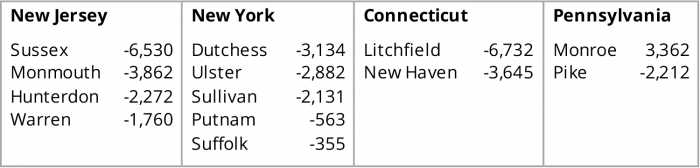

Almost three quarters (74 percent or 514,000 people) of this increase took place in the urbanized regional core, while only one quarter (26 percent or 178,000 people) was captured by the suburban ring. Thus, the overwhelming suburban dominance of post-World War II population growth appeared to succumb to urban resurgence following the end of the Great 2007-2009 Recession. Most startling was the actual population decline that took place in the outer perimeter counties of the metropolitan region, places that had once experienced substantial development pressures when twentieth century metropolitan growth pushed ever outward. These are graphically illustrated in the maps of the linked report. The following are the population losses suffered by the 13 perimeter counties – out of an overall total of 27 suburban counties – in the 2010-2016 period:[4]

To put this “new” suburban averse/urban-centric growth pattern into historical perspective, a comparison to the 1950 to 1980 period – when rampant population dispersal and tract-house development reigned – is strikingly illustrative. Between 1950 and 1980, the region in total gained nearly 4.5 million people. Concurrently, the suburban ring added more than 5.3 million people while the regional core lost 860,000 people. Within the New York sector of the core, Manhattan (New York County) lost 27 percent of its population (-532,000 people), the Bronx lost 20 percent (-282,000 people), and Brooklyn (Kings County) lost 19 percent (-507,000 people). In the New Jersey sector, Hudson County had the greatest decline, losing 14 percent of its population (-90,000 people). Pervasive urban decline was the unquestioned reality of this earlier era.

However, reality ultimately changed with a vengeance in the twenty-first century. Each of the leading counties of postwar population decline became growth loci in the 2010 to 2016 period (Table 1). In order of absolute population gain, four urban counties stood at the top of the 35-county regional growth ranking: Brooklyn added 140,000 people, the Bronx added 81,000 people, Manhattan added 73,000 people, and Hudson added 50,000 people. Demographic reversals are rarely so dramatic.

Disruption to the Reversal

But between 2016 and 2017, this “new” geographic pattern of growth reversed itself (although the longer 2010-2017 seven-year trend still showed regional core dominance). The suburban ring (+32,000 people) captured 62 percent of the region’s total 2016-2017 population increase (+52,000 people), while the regional core (+20,000 people) accounted for just 38 percent. Within the four-state suburban ring, it was the New Jersey sector that by far accounted for the largest share of growth: 17,000 people out of a total suburban ring gain of 32,000 people. Within the regional core, it was the New York City sector whose growth most dramatically declined. In fact, Brooklyn experienced an absolute population loss (-2,100 people) in 2016-2017, after gaining 140,000 people during the preceding six-year period (2010-2016). Moreover, except for Suffolk County in New York, each of the perimeter counties showed improvement between 2016 and 2017, either reducing the scale of their losses or returning to growth.

Discussion and Questions

Obviously, a single year’s metric “does not a trend make.” Nonetheless, there are now intriguing questions confronting future real estate realities. Was 2017 a new demographic inflection marker in the four-state metropolitan region’s post-2010 pattern of strong urban population growth and extended suburban malaise? Is the region’s twenty-first century urban population resurgence headed for a lull as “de-suburbanization” appears to be waning? Are the “burbs” gaining renewed traction again after faltering badly during the first six years (2010-2016) following the Great Recession? Are we returning to the familiar twentieth century suburbanization settlement norms? Were visions of an emerging demographic landscape of contracting outer-suburban communities increasingly dominated by aging households premature? Have resurgent communities in the urban core – supposedly the “new” postsuburban dynamic – become rapid victims of their own remarkable successes? Such successes may have escalated shelter costs so dramatically and so rapidly that new and major inhibitors to further growth may have emerged.

A host of additional questions remains to be answered. Are millennials – a driving force behind the region’s (and nation’s) recent urban reawakening – not actually allergic to human-driven personal vehicles, lower-density domiciles, and other suburban appurtenances as they enter the family-raising stage of the life cycle? Have suburban communities finally started to create the amenities desired by new lifestyle preferences? Was the suburbanization hiatus simply a result of mobility constraints stemming from the deep economic aftershocks of the Great Recession, as well as the credit and mortgage constraints that characterized post-recession financial reforms? Have the post-2010 urban preferences, in addition to producing demand-driven cost and price increases, also creating infrastructure overloads that are starting to inhibit the continued robust growth in the regional core? Or, again, are the 2017 survey numbers simply a one-time blip? Unfortunately, extant crystal balls at present do not reveal definitive answers to these questions. A complex matrix of evolving intersecting forces will continue to be at work reshaping our real estate future, producing new opportunities, new winners, and new losers.

[1] James W. Hughes, Joseph J. Seneca, and Will Irving, The “Burbs” Bounce Back “Trendlet” or “Dead Cat Bounce”? (Rutgers Regional Report 39, August 2018).

[2] William H. Frey, “US population disperses to suburbs, exurbs, rural areas, and “middle of the country” metros,” The Avenue, Brookings, March 26, 2018.

[3]James W. Hughes and Joseph J. Seneca, The Receding Metropolitan Perimeter: A New Postsuburban Demographic Normal (Rutgers Regional Report Number 37, September 2014).

[4] Monroe and Pike counties in Pennsylvania lie just west of the Delaware River, and encompass the region know as the “Poconos.” During the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s, they became New Jersey’s “growth frontier,” as residential development spilled over into this more affordable and less development-restrictive territory that was within commuter range of New Jersey’s growing suburban economy.