Balancing modern currencies and global monetary policies

In his testimony last week Fed Chair Jerome Powell was asked about his views on the value of returning to the gold standard, as well as his view of how the Fed sees Facebook’s proposed digital currency Libra. The gold standard came up because one of President Trump’s nominees to serve on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors is a longstanding advocate of returning to a gold standard. On the other hand the proliferation of digital currencies is a notable departure from currencies defined and backed by sovereign governments and is a direct challenge to fiscal and monetary policy that tax, spend, stimulate or restrict based on a common sovereign currency. An unregulated and widely used currency also poses a systemic threat for which government authorities will inevitably be left holding the bag if and when there is a problem. Powell was peppered with concern from both sides of the political aisle during his semi-annual testimony and he confirmed the Fed is in communication with Facebook, as well as other US and international banking regulators. Advocates of gold standards and decentralized currencies have a point in worrying about the limits of monetary and fiscal policy in a world of fiat currencies and flexible money supply, but neither provides a panacea or a realistic alternative. Instead, a more likely route is that proposed by the current chief of the Bank of International Settlements Augustin Carstens who recently noted that central banks will need to issue their own digital currencies sooner than previously thought.

The role of currency

In Economics 101 you learn that currencies serve three key roles in a market economy. Money serves as a unit of account that allows people to compare the value of different goods and services. It serves as a medium of exchange that facilitates the trading of goods and services, and it serves as a store of value that allows the transfer of value across time. It is easy to take the functional role of money for granted, but a society that collectively trusts in currency to fulfill these functions can move from a subsistence oriented economy unlocking tremendous efficiencies and growth potential by allowing people to specialize in what they do best. Money is a powerful force, but it is also subject to the whims of confidence, which in turn depends on the credibility of the entity issuing and managing the currency. The ability of currency to fulfill its functions is a delicate equilibrium whereby the majority of participants in an economy must trust and use it; it is a social contract that binds people together.

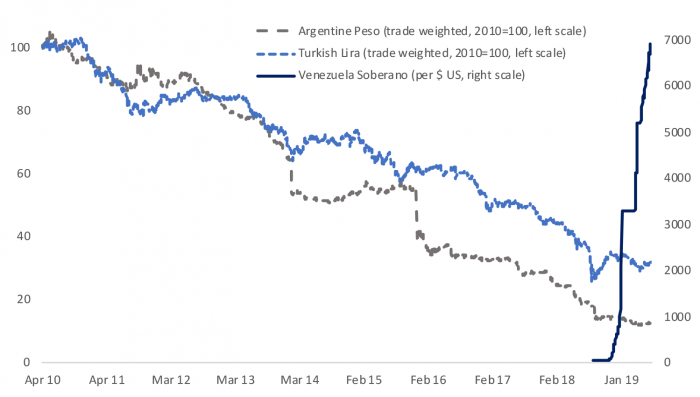

Figure 1: A Number of Countries Are Struggling with Loss of Confidence and Currency Depreciation

When governments that issue currencies mismanage the institutions and policies established to protect the stability of the currency’s value, the social contract can break down with real consequences for the economy. Figure 1 shows that some recent examples where trust in a currency is under pressure. The trade weighted value of the Turkish Lira has declined 70% since 2010 while the Argentine Peso has declined 87%. The Venezuelan Soberano was established in August 2018 to replace the Bolivar Fuerte in an attempt to address hyperinflation and restore stability. It doesn’t appear to have had the desired effect. A decline in the value of a currency can help stabilize a country’s economy as it makes its exports more competitive, but countries that suffer a loss of confidence and a currency crisis often see reduced investment and disruption to economic activity. Argentina has experienced an economic and currency crisis that required multiple IMF assistance packages. The country has seen steady declines in real GDP per capita since 2010 even as the global economy has continued to recover. Venezuela is in a full-blown currency and economic crisis although there have been no official statistics since 2014 so we can’t quantify the resulting impact on the economy. Turkey has managed to grow but has done so with a great deal of borrowing that may leave it vulnerable to a correction and it continues to enact policies that shake confidence in its currency. Their latest move that depressed the value of the Lira was the firing of the head of their central bank.

The rise and fall of the gold standard

As the Industrial Revolution progressed and international trade increased there was a greater need for confidence in and convertibility between various national currencies. Most countries used fiat currencies, that is currencies with no intrinsic value, but gold and silver were used by different countries to establish a stable value for and create trust in their fiat currencies. England formally adopted a gold standard in 1819 and the US followed in 1834. Industrialization, specialization and international trade were a relatively new way of life for the global economy and one that was greatly facilitated by a stable currency. Even though gold arguably doesn’t have much in the way of intrinsic value in terms of meeting the consumption needs of households, gold had a long history serving as a currency and convertibility helped confidence in fiat currencies take root thereby facilitating unprecedented growth and development.[1]

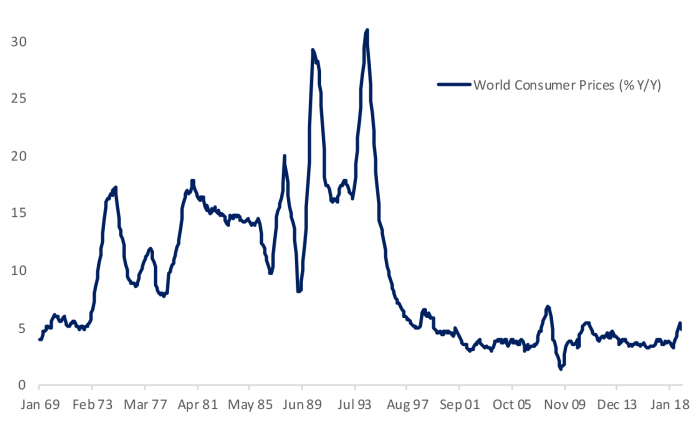

Figure 2: The End of the Gold Standard Saw Inflation then Price Stability

Under the gold standard countries guaranteed convertibility of their currency into gold at a fixed rate thereby ensuring the money supply, price level and exchange rates between currencies remained more or less fixed over the medium term. However, this meant greater volatility in short-term prices and the real economy to ensure the fixed price level and exchange rates held, and it also meant a shock in one country would be transmitted globally. Having a currency tied to a commodity like gold also leads to capricious shocks to the economy tied to the supply of gold. When the California Gold Rush led to an increased supply of gold it increased the money supply and the price level in the US which made exports less competitive leading to a trade deficit and an outflow of gold that brought prices back down.

While the gold standard helped establish confidence in and adoption of fiat currencies around the world, it limited the ability of monetary or fiscal policy to respond to shocks to the economy. This became evident during the Great Depression and World War II and the Bretton Woods system of monetary management was negotiated among 44 countries in 1944. The Bretton Woods system created a system of currencies that were still tied to gold and the US dollar, but created more flexibility to deviate from the fixed exchange rates to correct “fundamental disequilibirums” and the International Monetary Fund and World Bank were created to monitor and ensure compliance, as well as assist in crises. In 1971 the US terminated the Bretton Woods system and the world has operated in a regime of pure fiat currencies since.

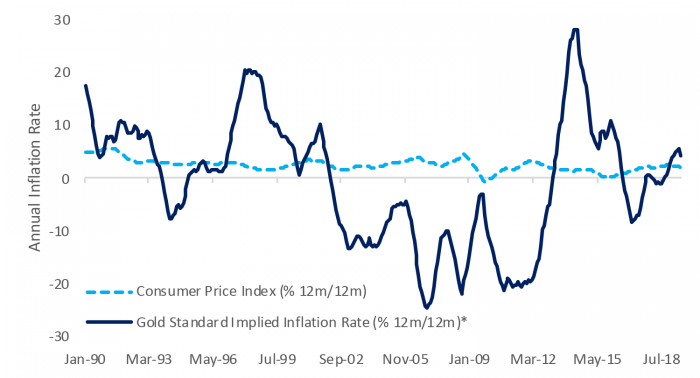

Figure 3: A Gold Standard Would Have Implied Massive Deflation in Recent Decades

The end of gold convertibility in 1971 was initially followed by a period of high inflation globally, that has since given way to low and stable inflation and the establishment of independent central banks most of which now have official inflation targets (Figure 2). Yet there is still a group of economists and policy analysts and commentators that advocate a return to the gold standard, not because of runaway inflation or breakdown in confidence in fiat currencies, but primarily to limit the flexibility of central banks and fiscal authorities from pursuing policies that risk implementing policies that could produce such outcomes. Judy Shelton who is currently U.S. executive director at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and whom President Trump names as a potential nominee to the Federal Reserve Board is a longstanding advocate of returning to the gold standard. In 2009 at the height of the Great Recession Shelton penned an editorial in the Wall Street Journal advocating for a return to the gold standard “because a gold standard stands in the way of runaway government spending” that would inevitably lead to inflation that would undermine the capitalist system. In the same editorial Shelton argued that privately issued currencies backed by gold should be allowed to proliferate and compete with the US dollar.

It is worth contemplating what a gold standard would have looked like in recent decades. Figure 3 shows the inflation rate implied by a gold standard (solid line) plotted against inflation actually experienced as measured by the Consumer Price Index (dashed line). This figure illustrates the very reason countries abandoned the gold standard. The chart highlights that when the dollar is pegged to keep the price of gold fixed, inflation and the associated adjustments in the real economy would be excessively volatile. To hit home the point, a gold-standard would have implied breathtaking deflation in the decade ending in 2010. Prices would have fallen 73% over that decade, so that a house worth $250,000 in 2000 would have been worth $67,500 by 2010, or a person making $100,000 in 2000 would have been making $23,000 by the end of the decade. The disruption to both Main Street and Wall Street would likely have been so severe that policymakers almost certainly would have backed off the gold standard after just a few years.

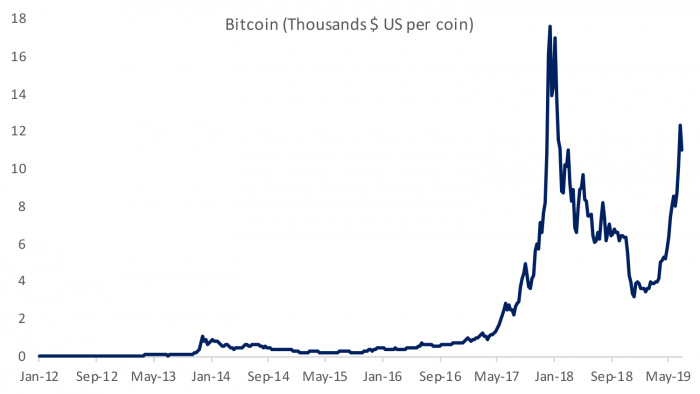

Figure 4: Bitcoin’s Volatility is a Barrier to Serving as a Currency

Prospects for digital currencies

While not backed by gold, cryptocurrencies have some things in common with the gold standard and potentially provide the competition to the dollar Shelton was seeking in 2009. Cryptocurrencies are assets purchased by existing currencies that are backed by decentralized technology and organizations and seek to serve the three functions of a currency over time. Like gold their supply is intended to be relatively fixed and controlled by designated “miners.” Purveyors of cryptocurrencies generally see being outside the regulatory net as an advantage, and the underpinning technology as more secure and protective of longer-term value. Like gold standard advocates they tend to see the world of government-controlled fiat currencies as fraught with policy risk. In practice the value of currencies such as Bitcoin have been extremely volatile, which has served as a barrier to serving as a store of value, unit of account and medium of exchange (Figure 4).

In a potentially important step forward for cryptocurrencies, Facebook announced in June that it plans to launch its own digital currency Libra in the first half of 2020. Libra will use the same blockchain technology used by Bitcoin, but it will be backed by reserves of existing currencies. People can make deposits in US dollars of British Pounds or Japanese Yen in exchange for an equivalent value in Libra and then use Libra to buy and sell goods and services. Facebook is designing Libra with the understanding that the success of currency is based on widespread acceptance and confidence. Design features include that Libra will be controlled by a consortium of 100 private organizations including non-bank financial firms such as Visa, online service providers such as Spotify or Uber, cryptocurrency wallets, venture capitalists and charities such as Kiva and Mercy Cops. Facebook wants to convince both the public and potential consortium members that privacy will be protected and consortium members will have full control by creating a separate subsidiary Calibra to operate Libra. What Facebook hopes to offer to attract users is the ability to buy and sell goods and services on a global scale much faster and cheaper than they currently can through either banks or cryptocurrencies. Facebook doesn’t plan to charge a transaction fee and will make money off the creation of Libra through greater scale and ad revenues.

The more successful is Libra, the more of a vested interest policy makers around the world will have in monitoring and regulating it and Facebook acknowledges that unlike existing cryptocurrencies, Libra will need to be transparent and comply with anti money laundering and other regulations. Fed Chair Powell was peppered with concern from both sides of the political aisle during his semi-annual testimony and he confirmed the Fed is in communication with Facebook, as well as other US and international banking regulators. A widely used currency outside the control of government poses a direct challenge to monetary and fiscal policies that tax, spend, stimulate or restrict based on a common currency. An unregulated and widely used currency also poses a systemic threat for which government authorities will inevitably be left holding the bag if and when there is a problem.

The early history of money in modern industrial societies was a bid for confidence and stability. With confidence in fiat currencies secured, recent decades have seen policy makers pursue flexibility in money supply and exchange rates in order to achieve economic objectives. While small countries still struggle with failures of confidence and currency crises, those that have achieved reserve currency status have used the privilege to finance the costs of an aging society in the case of Japan, or to smooth through self-inflicted financial crises in the case of the US and Europe, without any resulting loss of confidence in the currency. Advocates of gold standards and decentralized currencies may have a point in worrying about the limits of monetary and fiscal policy in a world of more flexible money supply, but neither likely provides a panacea or realistic alternative. Instead, a more likely route is that proposed by the current chief of the Bank of International Settlements Augustin Carstens who recently noted that central banks will need to issue their own digital currencies.

[1] For a summary see “The Gold Standard” by Michael Bordo in Econlib’s Economic History collection.