How trade conflicts might dampen economic momentum

The US economy has been running hot. The latest confirmation came from a May employment report that showed the unemployment rate at the lowest level since 2000 on its way to levels not seen since the 1960s. With the current expansion officially becoming the second longest in the post-War period, observers have been speculating about potential catalysts for the next downturn. A trade war is an obvious candidate, particularly since recent economic momentum has been concentrated in goods-producing sectors that are tightly integrated with the global economy and vulnerable to disruptions and conflict in trade. The US has recently announced tariffs on our closest allies and trading partners, who in turn are planning a round of retaliatory actions. A sustained trade conflict will likely result in higher inflation, a profit squeeze and greater uncertainty that dampens investment. The Fed will face a conflict between reacting to higher inflation with higher rates or slowing the pace of rate hikes due to a hit to consumer purchasing power. We suspect the developing trade conflict will stop short of causing the next recession, but it is likely to dampen the recent robust economic momentum.

The May employment report was yet another data point confirming the US economy is running strong. The report showed employers added 223k jobs in May. To hold the unemployment rate steady, only about 110k were required to absorb new entrants to the labor market. Consequently, the unemployment rate dropped to 3.8%, the lowest reading since 2000. With the pace of job gains running at 197k per month over the past year and showing no signs of slowing, it is likely the unemployment rate will continue to decline and reach levels not seen since the late 1960s.

Despite its fragility and ebbs and flows, the current recovery officially becomes the second longest post-World War II expansion this quarter. The length of the recovery has spawned speculation about what might lead to its demise and spur the next recession. One candidate is the possibility that the recently announced round of tariffs on aluminum and steel and the retaliatory moves that are already in the works from our trading partners could escalate into a trade war. The US has relatively low exposure to trade compared with other countries, but the composition of the recent hot streak in the economy suggests we may indeed be vulnerable to trade disruptions.

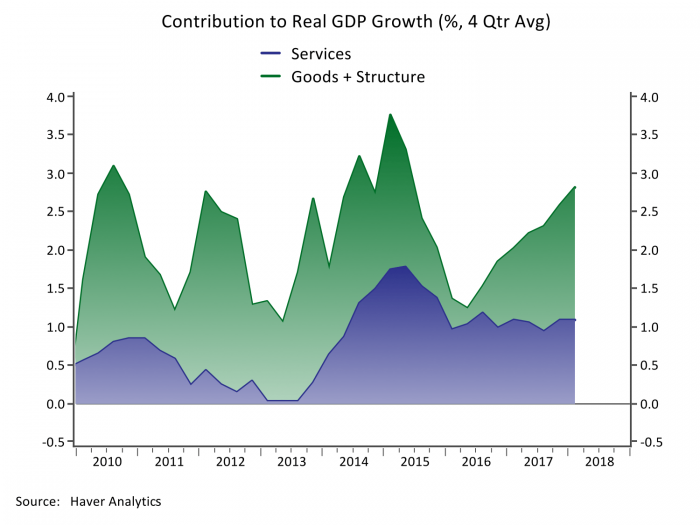

Figure 1: The Goods Economy has Powered the latest Pickup in Growth

Goods Producing Sectors Have Been Running Hot, and Are vulnerable to Trade Wars

Exports and imports combined comprised 27% of GDP last year, so there is plenty of scope for disruption. Furthermore, the value of trade in goods is nearly four times the value of trade in services, and it is the goods economy that has powered growth of late. Figure 1 illustrates the combined contribution of goods- and services-producing sectors to overall GDP growth. After an uncharacteristic anemic stretch early in the recovery, the services sector has been chugging along in a fairly stable manner in recent years adding roughly 1 percent to GDP growth.

The goods-producing sectors include manufacturing, mining and energy exploration and production, and construction. The goods economy typically leads the economy into and out of recessions. Goods production requires inventory management, and consumer demand for durable goods in particular is more discretionary and subject to greater cyclical swings that are then perpetuated through inventories, production and employment. The goods sector had a typically strong start to the recovery, then slowed nearly to a halt in 2015 and early 2016 before rebounding sharply over the past year. The goods economy added 1.74% to GDP growth in the four quarters ending in Q1, 2018 as compared to 1.1% from the services sector. If the goods economy were to get hit by global trade disputes it would not necessarily drive the economy into a recession, but we could see growth and employment cool considerably.

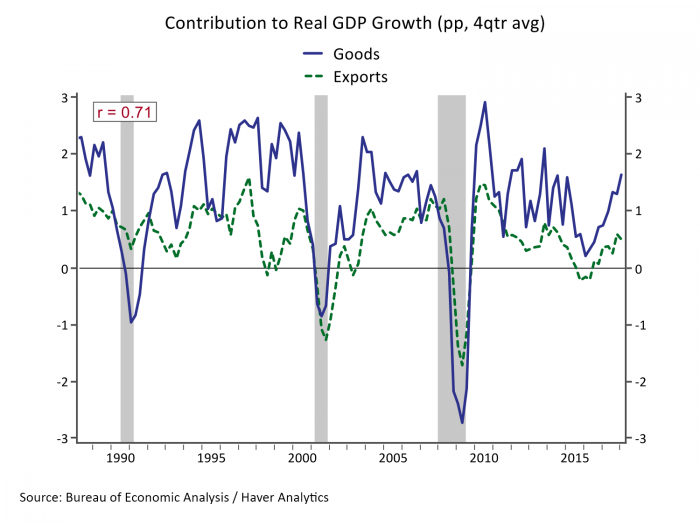

Figure 2: The Goods Economy is Powered by Global Demand

The goods economy is far more integrated with the global economy than are the service sectors. This is illustrated in Figure 1 which plots the contribution to GDP growth from goods sectors and from exports. These two measures are not mutually exclusive. Quite the opposite in fact , there is a great deal of overlap. While the manufacturing share of employment has declined from 20% in the early 1980s to just 8.5% today, the US has remained productive and competitive in high value-added capital equipment, resulting in the value of exports rising as a share of GDP from 9% in the early 1980s to more than 12% in recent quarters. The US supplies the world with aircraft, agricultural and medical equipment and a variety of industrial components that could become targets for tariffs in coming months.

A Trade War’s Channels of Impact

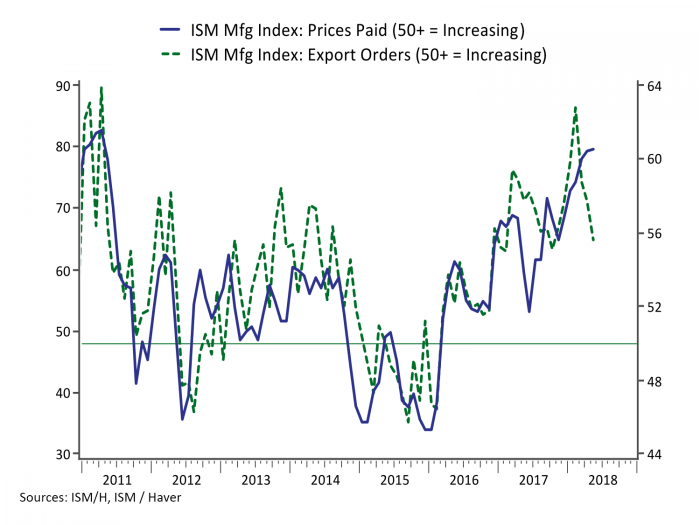

The most immediate impact of a round of tariffs and counter-tariffs would be to raise the prices of the affected goods for both foreign and domestic consumers. The steel and aluminum tariffs are levied on imports, but since the US is a net importer, domestic producers cannot satisfy demand and the resulting scarcity drives up even the price of domestically produced metals. Domestic steel and aluminum producers are happy about the higher prices they will receive but automakers, aircraft manufacturers, commercial real estate developers, and others who use steel and aluminum as inputs see higher prices and must determine whether they can pass those on to their end consumers or whether they will have to absorb the increased costs in their profit margins. Respondents to the May manufacturing survey conducted by the Institute of Supply Management reported a steady increase in prices paid for inputs and a third straight decline in export orders (Figure 3). The overall index remined consistent with robust manufacturing growth, but the tariffs have yet to take full effect and retaliatory tariffs from trading partners are still in the planning stages.

Figure 3: Tariffs Would Raise Prices and Weaken Demand

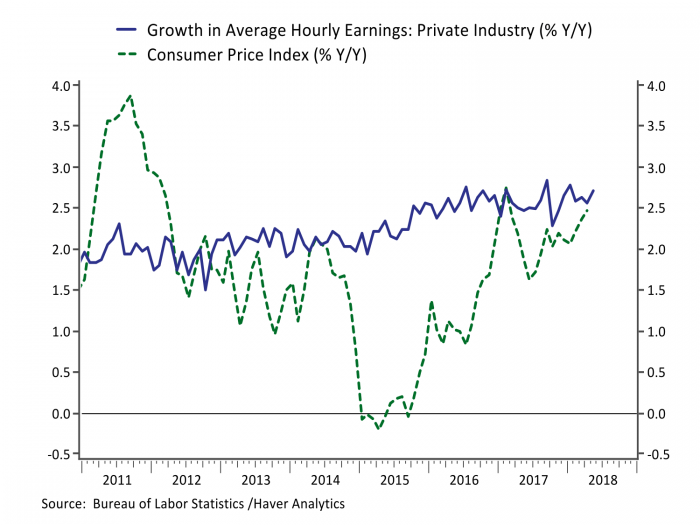

Consumer purchasing power would be hit if producers pass increased costs on to consumers. The strong labor market has just begun to show through in a modest uptrend in wage growth, but this has also come with rising inflation from higher gas prices. Figure 4 shows that the modest improvement in wage growth is just barely outpacing higher inflation, leaving consumers with meager improvements in real purchasing power. A trade war that resulted in higher prices on a broad range of consumer goods would hurt consumers, who comprise 70% of the economy, which in turn could spill over and dampen demand in the service economy. Given that goods account for a third of the consumer basket and the pass through will be limited, we expect a moderate and temporary boost to inflation. That will dampen the benefit consumers enjoy from a stronger wage trend but stop short of derailing consumer sentiment and spending.

Broad-based inflation from tariffs could potentially put the Fed in a bind. The Fed has been able to raise rates slowly in part because consumer inflation has run persistently shy of their 2% target. Inflation from tariffs could threaten to take inflation above target which would suggest a faster pace of interest rates increases may be warranted. However, if inflation is not matched by wage growth, then it could destroy demand and weaken the economy. The Fed will have to tread carefully. For now we think the Fed will split the difference by proceeding with its planned course of gradual rate hikes.

Figure 4: Consumers Would Suffer if Inflation Exceeded Wage Growth

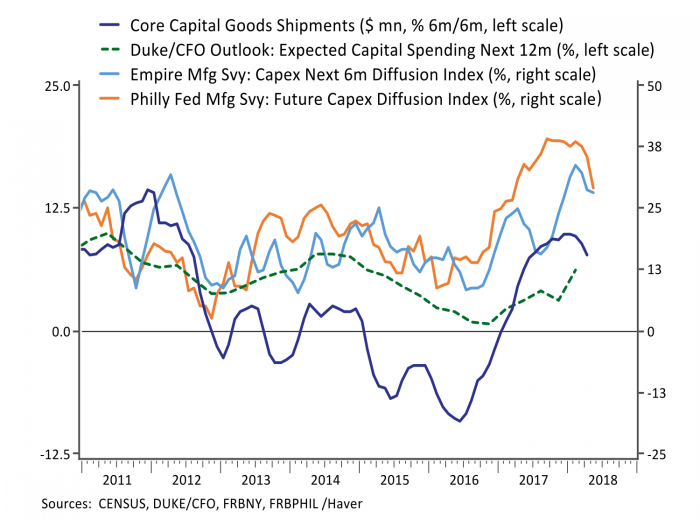

Trade conflicts also have the potential to offset incentives for investment put in place by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Confidence among manufacturers has soared in recent years, first on the synchronized global recovery that took hold in 2016 and then on the prospect for reduced regulation and tax cuts from the Trump Administration. Figure 5 shows several survey measures that show that improved confidence led to increased intentions to invest among manufacturers and CEOs and confirms that these survey measures were matched to some degree in the hard investment data. As the year has unfolded, the prospect of trade conflicts has coincided with a moderation in intentions to invest in capital expenditures as well as actual investment. In effect the trade conflicts are likely to offset and crowd out some of the boost to growth that was supposed to result from fiscal stimulus through a direct cost channel, as well as reduced confidence and increased uncertainty about the future that would results from a prolonged trade conflict.

Figure 5: Trade Wars Could Dampen Confidence and Investment

There has been longstanding bipartisan agreement that China has engaged in unfair trade practices. Taking China on and attempting to renegotiate the terms of our trading relationship could result in near term pain in exchange for longer term gain. The more recent moves to penalize allies had less political support or economic rationale and poses a threat to the recent robust momentum in the US economy. We think the result will be growth that comes in shy of the robust expectations that came on the back of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but trade conflicts will stop short of being the catalyst for the next recession.