The correlations between weakness in consumer spending and inflation

Are the recent low inflation readings a signal of weakening consumer demand or a transitory development? The answer is key for thinking about which way the economy and interest rates are headed. In this third blog examining recent inflation developments, I take a look at discretionary categories of consumer spending and pricing and find that there is indeed a correlation between weakness in consumption and inflation. Softer consumer spending comes despite a falling unemployment rate, rising stock markets and elevated levels of consumer confidence. Getting inflation to the Fed’s 2 percent target may require patience on the part of the Fed, but also greater exuberance on the part of the US consumer.

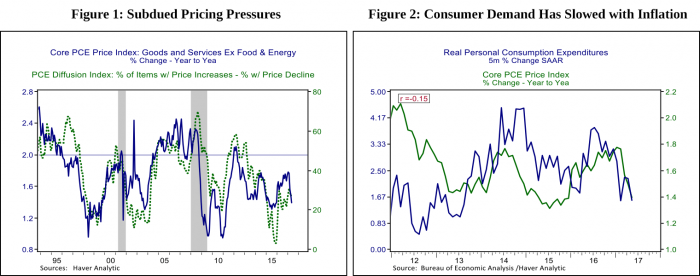

In a recent blog I referred to the diffusion index shown in Figure 1 which subtracts the percent of items in the basket of items with falling prices from the percent of items with rising prices. I suggested the fact that the diffusion index remains so low is an indication of price sensitivity among consumers. The chart plots the diffusion index against the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index and a horizontal line at the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Historically we haven’t hit the Fed’s 2% target without the diffusion index closer to 50. In this blog I dig into my prior assertion that some of the weakness in inflation reflects price sensitivity and subdued demand in a little more detail by examining an item from each of the main categories of consumer spending; durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. I focus on discretionary items instead of necessities and examine the relationship between pricing and demand to see which one leads in order to get at whether the recent low readings on inflation are in fact an indication of price sensitivity and subdued demand or one off developments to be mainly ignored.

In the standard macroeconomic framework for analyzing business cycles and inflation, inflation is a lagging economic indicator rather than a signal of the current state of affairs. As the economy recovers from a recession and the unemployment rate falls to its long-term sustainable rate, tighter labor market conditions lead wages to rise making consumers less price sensitive and allowing firms to raise their prices. Strong labor markets are a leading signal of robust demand and inflation dynamics in this framework. If this wage-price push gets out of hand there can be an unwanted inflation spiral, something Fed policy had to reign in by raising the federal funds rate to almost 20% in the early 1980s.

In the current cycle, the Fed is confronting the opposite problem, that of wages and prices getting stuck at a pace that is too subdued leaving interest rates stuck close to zero and the Fed with limited and unconventional options to stimulate the economy if and when we confront the next recession. Understanding whether low inflation is primarily a signal of weak demand as opposed to transitory, structural or global factors outside the Fed’s control will help the FOMC determine if it should keep monetary policy accommodative to support stronger demand growth and higher inflation. Figure 2 confirms that both inflation and the growth of real consumer spending have indeed slowed in tandem thus far this year, however the relationship is not perfect and this can’t be taken at face value as cause and effect. It is particularly surprising that consumption has slowed at a time when the labor market is humming along, consumer confidence has perked up, and the stock market and rising home prices are boosting household balance sheets.

Cars: A Flexible Necessity

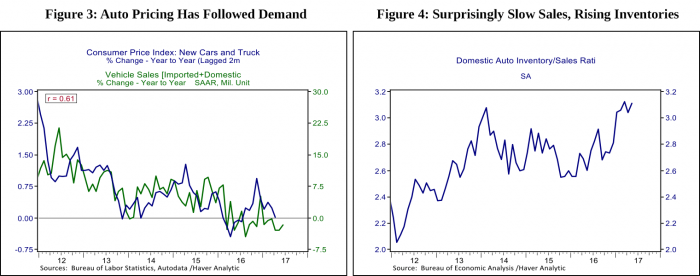

Cars are a necessity for most households. However, the timing of a vehicle purchase is flexible. When the economy falls on hard times consumers tend to pull back on car buying, choosing instead to extend the lives of their existing vehicles. Figure 2 shows that after years of robust growth, car sales peaked at an impressive 18.4mn SAAR pace in December 2016 and have been declining steadily in the first half of this year. Car pricing can be influenced by a number of structural factors, such as the bailout and restructuring of the auto industry during the Great Recession. I focus on the relationship between car demand and pricing over the past five years of the recovery and find that auto pricing has responded to demand rather than the other way around. After putting off car purchases during the recession and early stages of the recovery, consumers have been satiating their pent-up demand for new autos in recent years and have been less price sensitive allowing car makers to restore both production and profit margins. The slowdown in auto sales this year came as an unwelcome surprise to many automakers who reportedly increased the pricing incentives they are offering consumers for the 26th straight month in May according to JD Power. Auto production can’t turn on a dime and Figure 4 illustrates that inventories are piling up despite the discounts offered suggesting continued discounting in the months ahead.

Women’s Apparel: Competition and Restructuring

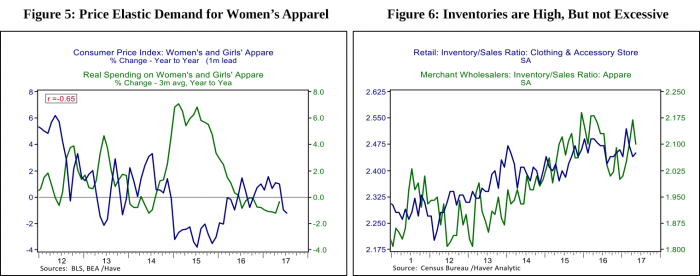

Women’s apparel is one of the most discretionary items in the consumer basket according to retail analysts. How much a woman spends on clothing in a given season or year is subject to a great deal of discretion, and the retail industry is both intensely competitive and in a state of dramatic restructuring. This discretion and competition manifest themselves in the inverse and contemporaneous relationship between prices and demand shown in Figure 5; women will buy clothes when they get good deals. In 2014-15, deals on clothing, which is mostly imported, benefited from a strong dollar. The fading of the strong dollar tailwind to pricing coincided with a pronounced slowing in spending in 2016. A weaker dollar over the past year hasn’t really translated into higher prices in part because of the intense competition in the industry, the highly elastic demand and the role technology is playing in transforming the industry. Figure 6 indicates inventories are higher at the wholesale and retail level, but over a couple of years suggesting rather than sharply this year that apparel may not need dramatic discounting to clear the racks. Nonetheless, industry forces are likely to keep apparel inflation in check despite a weaker dollar of late.

Competing Forces in Restaurant Pricing

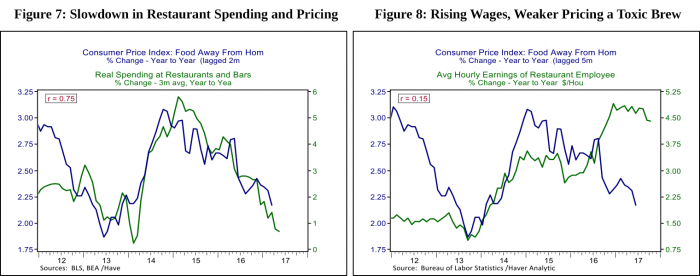

Restaurant spending is a service category that is also highly discretionary and competitive, and the amount of restaurant services supplied is highly elastic and responsive to demand. Figure 7 shows that in recent years pricing has followed the ebbs and flows of demand. Prices rose with demand in part because of intensifying wage pressures for retail workers as labor is the biggest input to restaurant services (Figure 8). The continued slowdown in restaurant spending is perhaps the most worrying demand indicator examined in this blog because it corroborates the predictions of macroeconomic theory that were just starting to come to fruition in recent years. The fact that consumers continue to exercise caution in this highly discretionary category despite all the positive economic forces in their favor is striking, and consumer caution combined with rising costs doesn’t bode well for the profitability of the restaurant industry.

A romp through the details of consumer inflation suggests that, at a minimum, the recent low inflation readings are consistent with the consumption slowdown seen in the first half of 2017, and may not turn around without more exuberance on the part of consumers. One indication of consumer caution is that the personal saving rate has risen to 5.5% in May from 4.5% in December despite the unemployment rate falling to 4.4% in June from 4.7% in December and stocks making new records almost every week. Fed speakers have indicated patience on interest rates for now in response to these surprising developments. The strength and required discounting during the back to school shopping season, second only to Christmas in its importance to US retailers, will be a key test of true put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is consumer sentiment. Whether auto sales stabilize at still healthy levels or continue to drift lower will also be a litmus test of where the economy is heading into H2. In an era where so many academic models have been off the mark, the pragmatic economists that make policy at the Fed for the real world will have to think on their feet and read the signs.