Yes. But an aging population may make a recovery harder too.

The average age of the US population has been rising rapidly in recent decades on the back of declining birth rates and increased life expectancies, a situation common to most advanced countries and many developing ones. An aging society means an increased share of spending devoted to health care and a growing share of the labor force employed in the health care sector, which are much less subject to cyclical swings. This year despite slowing GDP growth health care employment has nudged modestly higher, and now accounts for more than a third of all jobs created given a pronounced slowdown in hiring in other sectors. The stability in health care demand has effectively served as a buffer against headwinds from a slowing global economy and rising uncertainties around trade policy. But while an aging society may confer greater macroeconomic stability, it also means the traditional monetary policy tools used to pull an economy out of recession are likely to be less effective. Household debt continues to grow more slowly than income, reflecting a number of factors including an aging population, and the responsiveness of mortgage demand to interest rates has fallen by more than half. Interest rate policy isn’t completely powerless; housing is poised to make its first positive contribution to growth in Q3 in a year and a half as home sales and construction have seemingly responded to the 100 basis point decline in mortgage rates since last fall. Monetary policy has been effective in helping offset recent headwinds but will likely struggle to deliver the needed impulse if faced with a more severe downturn.

An aging society means a more stable job market increasingly tilted toward health care

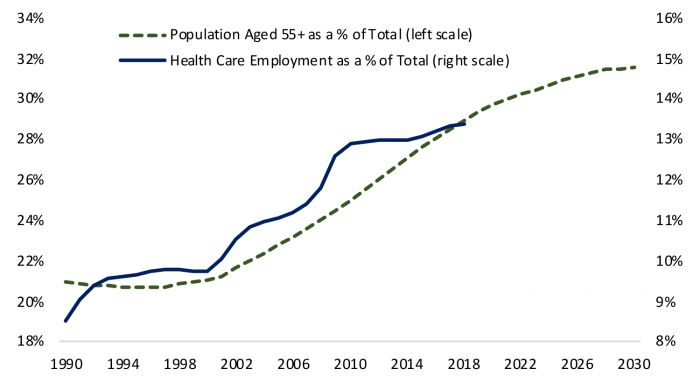

Declining birth rates and rising life expectancies in recent decades mean the US population has been and is projected to continue growing older on average, an outlook shared by most advanced countries. Figure 1 illustrates that the share of the population aged fifty-five and older stands at 29% in 2019, up ten percentage points since the early 1970s. That share is projected to growth to close to a third of the population by 2030. As the population ages, the share of household budgets going to health care goods and services has risen from eight percent in 1970 to 21 percent in 2019. Figure 1 also illustrates that as the population ages and more consumer spending is devoted to medical expenditures, a growing share of the workforce is employed in the health care industry. As of August, 13.5% of the workforce was employed in health care, up from 8.4% in 1990 and likely to continue rising in the years ahead as the population continues to age. The employment share is understated as it captures only those employed in the private delivery of health care services and not those employed by government entities or engaged in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and medical devices, whereas the spending share referenced is for all medical care goods and services.

Figure 1: An Aging Population Means a Greater Share of the Economy Employed in Health Care

The rising share of health care employment doesn’t necessarily have implications for overall employee compensation; the average hourly wage for the health care and social assistance sector stood at $27.85 in July, just a little shy of the national average for the private sector as a whole of $28.00 per hour. Wages in the health care sector have been growing more slowly at 2.0% y/y through July as compared to 3.3% y/y for all private sector employees. The average wage of the health care sector masks a wide dispersion among segments and occupations. Physicians and dentists enjoy wages well above the national average while wages for workers in home health care and at nursing and residential care facilities earn well below the national average.

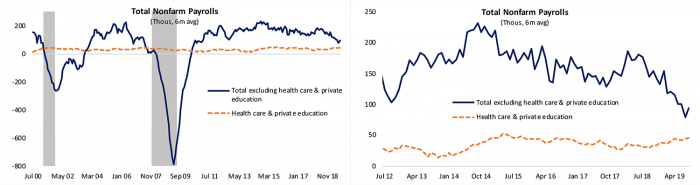

Figure 2: An Aging Population Means Increasing and More Stable Health Care Employment

Health care spending doesn’t ebb and flow with the business cycle as much as other types of consumer expenditures. As a result, as illustrated in the left panel of Figure 2, hiring in the industry is also considerably more stable than for the economy as a whole. The private health care and education industry has never seen an annual job loss since 1945, whereas persistent job losses are one of the criteria used by the National Bureau of Economic Research in determining when a recession has started and ended.

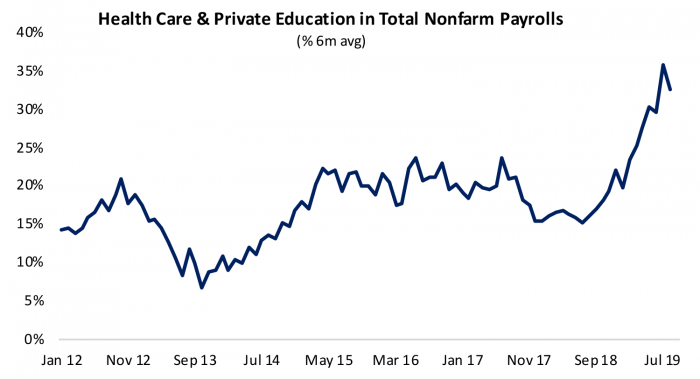

Indeed, a recent slowdown in hiring was one contributor to recent speculation the US economy may be facing a rising risk of a recession in the next twelve months. The right panel of Figure 2 illustrates that while the average pace of hiring outside the health care industry has slowed sharply this year, health care hiring has actually strengthened just a touch. Figure 3 underscores the point, showing that hiring in the private health care & education service sector has accounted for more than a third of all hiring in 2019, a substantially higher share than at any other point in the ten-year recovery. The current share of health care hiring may not be sustainable given it so far outstrips the spending share, but it has serving as an essential buffer to weakness elsewhere so far this year. As other sectors including manufacturing and leisure and hospitality face headwinds from a weakening global economy, the health care sector enjoys an autopilot dynamic; medical spending is financed by private payroll deductions and government insurance payments leaving it less susceptible to the sort of shifts in sentiment and rising caution that contribute to cyclical pullbacks. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid services estimates that only 10% of overall health care spending in the US is financed out of pocket by consumers.

An older society more dominated by health care spending means the economy is slower growing, but also potentially more stable. The manufacturing sector in the US has experienced three recessions since the current recovery began in 2009 as measured by the Institute for Supply Management’s Purchasing Mangers’ Index and The Federal Reserve’s gauge of industrial production, but the broader economy hasn’t succumbed to the weakness.

Figure 3: Health Care Jobs Now Have Accounted for More Than a Third of Hiring in 2019

An older society is less interested in borrowing and less sensitive to interest rates

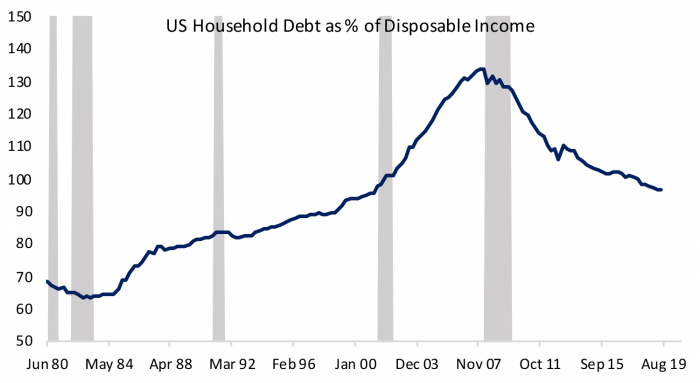

While an aging society may confer greater macroeconomic stability, it also means the traditional monetary policy tools used to pull an economy out of recession are likely to be less effective. The economists’ workhorse model of life cycle consumption predicts households will borrow and save when young and then spend out of accumulated saving when old. An older society will naturally be less interested in borrowing and therefore less sensitive to shifts in interest rates. Figure 4 shows that households continue to borrow more slowly than their incomes are rising. The ratio of debt to income for US households fell to 96.6% in Q2, the lowest level since 2001. The ongoing deleveraging of household balance sheets is not just a function of an aging society; I have noted in recent posts that student loans have crowded out the capacity to take on mortgage debt for many millennials; rising inequality means more economic resources are in the hands of wealthy households whose behavior and patterns of borrowing may not follow that predicted by simple life cycle models of consumer behavior, and tighter regulation in the aftermath of the financial crisis means credit is harder to obtain. Nonetheless when the household sector as a whole, which makes up 70 percent of the economy, is less inclined to borrow for a variety of reasons, it suggests the economy will be less responsive to interest rate policy.

Figure 4: Households Continue to Borrow More Slowly Than Their Income is Rising

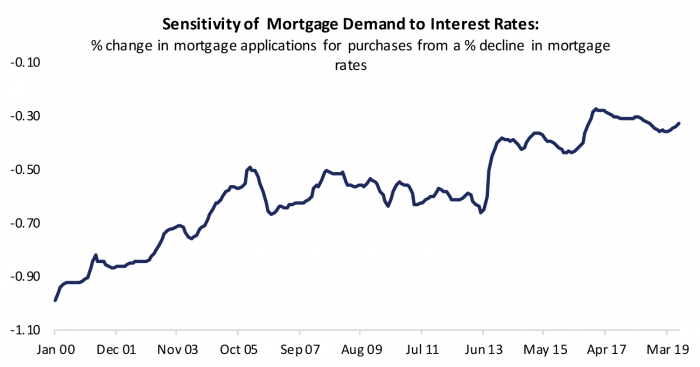

We test household responsiveness to interest rates by looking at the sensitivity over time of mortgage demand to interest rates. Figure 5 shows the results of a simple regression of the growth in mortgage applications for the purchase of a home on changes in mortgage rates, controlling for whether the economy is in recession and for the level and change in the unemployment rate (mortgage demand should move inversely with interest rates but when the economy is weakening mortgage demand may decline with interest rates). We estimate the relationship over ten-year rolling windows starting in 1990 through the most recent data for August. The results show that in the ten years ending in 2000 a one percent decline in mortgage rates was associated with a similar increase in purchase applications for mortgages; however that response has steadily moderated such that a one percent decline in mortgage rates is now associated with only a 0.33% increase in applications. Factoring in the fact that the average mortgage rate over the last 10 years is half of what it was in 2000 (4% versus 8%), the results of the regression suggest that a 100 basis point decline in mortgage rates would have led to a 12.3% increase in mortgage applications in 2000 while a similar move today will produce a 7% gain. In addition to an aging effect, responsiveness to near term changes in interest rates may be dampened if households now expect rates to remain low and feel less of a need to take advantage of a decline.

Figure 5: Demand for Mortgages has Become Less Sensitive to Interest Rates

Reduced sensitivity doesn’t mean interest rates are completely ineffective. Indeed after writing recently that weakness in housing was sending warning signals, the most recent data on home sales and construction show a positive, albeit moderate response to the roughly 100 basis point decline in mortgage rates from the peak last fall. Housing is on track to make its first positive contribution to GDP since Q4 2017. In addition to buying more homes, households have refinanced existing mortgages, boosting their disposable income. Monetary policy is helping offset some of the drag on manufacturing and investing from the global slowdown and the uncertainties tied to the trade war. The Fed may ultimately be successful in its bid to avoid a hard landing now, but if faced with a more severe downturn interest rate policy will likely struggle to deliver the needed offset.