Exploring a portrait of increased diversity and economic challenge

The Millennial Generation bears arguably the most lasting imprint of the Great Recession of any generation. They are currently aged 23 to 38, a period of life typically associated with some combination of rising earning power, marriage, home ownership, and children. Yet this generation differs from Generation X and Baby Boomers in key aspects that suggest lasting economic insecurity for many of its members. Millennials are much more diverse, and the role of women is undergoing seismic change. Women are getting married later, having fewer children later in life, graduating from college at higher rates than men for the first time ever, participating in the labor force at higher rates than prior generations, and seeing greater gains in real income than men (although they still lag behind in absolute terms). Millennial men have been challenged by sectoral and geographic change in the composition of available jobs and have seen declining labor force participation. It is a generation of more haves and have nots; inequality continues to rise and poverty rates among millennials are nearly twice that of Baby Boomers at a comparable age. Millennials have less wealth than prior generations at a similar point in life, reflecting delays in and lower rates of homeownership, and greater student loan burdens. Millennials continue living with their parents at record rates, a development that can only be partially explained by differences in economic and demographic characteristics. It remains to be seen whether Millennials will eventually see comparable rates of homeownership at later stages in their life, which has important implications for wealth accumulation and retirement security. There is still time for millennials to enjoy the benefits of rising real wages, particularly if the US manages to avoid a recession in coming years. The Baby Boomers also experienced the deep double dip recession of the early 1980s early in their careers and managed to recover over time.

The Millennial Profile: More Diversity and Economic Challenge

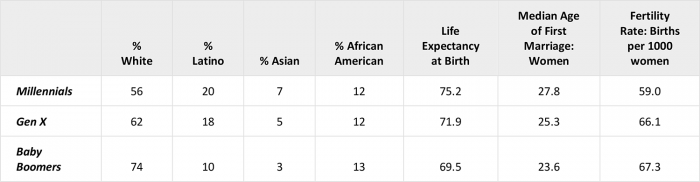

The Millennial generation is defined as those born between 1981 and 1996, making them 23 to 38 in 2019. The generation is noticeably different in their demographic composition, labor force activity and economic status from prior generations. Figure 1 provides a comparison of the demographic characteristics of Millennials with Generation X and Baby Boomers. Millennials are much more diverse racially, largely reflecting a rise in the share of Latinos and Asians. A study from the Brookings Institution also indicates there are far more interracial marriages (14% up from 10% in Generation X and 5% among Baby Boomers) and more Millennials speak a language other than English at home (25% up from 23% for Generation X and 11% for Baby Boomers). Millennials can expect to live longer and are getting married later and having fewer children later in life.

Figure 1: Demographic Characteristics by Generation

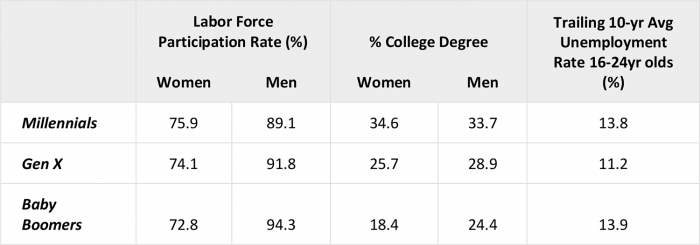

In addition to marrying and having children later, Millennial women are the first generation where a slightly greater share of women have college degrees than men and the gap between male and female participation in the labor force is the smallest ever. Figure 2 shows education and labor market characteristics at ages 25-34 and illustrates that Millennial men and women are both more educated, but the gain among women has been notably larger. Women’s labor force participation has risen steadily by generation while men’s has fallen by even more than female participation has risen.

Figure 2: Education and Labor Market Characteristics by Generation at Age 25-34

According to the labor force participation decomposition from the Atlanta Fed, about a quarter of the decline in male participation reflects increased sharing of household responsibilities, including raising children. An even smaller share is tied to longer period of schooling. Much of the decline is difficult to explain and may be tied to a shifting composition of available jobs from manufacturing and construction where men are employed at higher rates to health care and other service sector jobs where the gender balance of employment is more equal or even tilted toward women. The changing composition of jobs has come with a shifting geographic concentration toward urban areas, and not all workers have been able to move with the jobs. Research from the late Alan Krueger attributed some of the decline in prime age male labor force participation to rising substance and opioid abuse and disability claiming, all of which may also reflect in part the shifting nature of economic opportunity. Figure 2 highlights that the average unemployment rate experienced by Millennials in their early years in the labor force is notably higher than for Generation X, although more on par with Baby Boomers, who experienced the double dip recessions of the early 1980s.

Figure 3: Economic Status by Generation at Age 25-34

The current economic status of Millennial households is outlined in Figure 3 and compared to prior generations at a similar stage in life. While there is still a substantial gap in the real earnings of households headed by women than those headed by men, women have made notable gains whereas the real income of male-headed households has stagnated. The Gini Coefficient is a measure of how equally incomes are distributed across households that ranges between zero and one, where zero represents perfect equality and one perfect inequality. The United States has the highest amount of income inequality among advanced countries by this measure and it has risen more in recent years. Underscoring the inequality masked by median measures of income, the poverty rate among households headed by 25-34 years olds is also notably higher for Millennials than prior generations and suggests a nontrivial amount of economic distress.

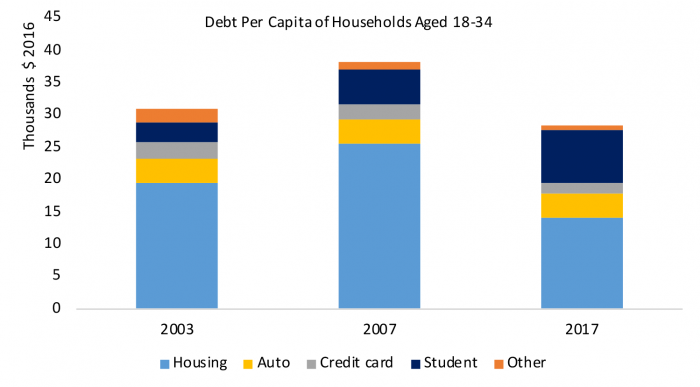

Figure 3 also shows that Millennial households have less real net worth, higher debt burdens relative to their incomes and noticeably lower rates of homeownership than prior generations at a similar age, even as homeownership has nudged up in the past two years. Figure 4 illustrates that the composition of debt among millennial households is also tilted toward student loans over mortgages, something we wrote about in a recent blog post. Both forms of debt represent investments that can generate returns justifying the risk of taking on debt, but the income statistics show that many households aren’t seeing a higher return yet in the form of increased real earnings, and a growing body of research finds that student loans crowd out the ability of many young households to invest in homeownership. This tradeoff has been exacerbated by tighter credit standards. Our prior blog post documented that banks have increasingly been lending to older, wealthier homeowners at the expense of younger borrowers with lower credit scores.

Figure 4: Millennials Have Higher Student Loan Debt, Fewer Mortgage Obligations

The Rise of Multi-Generational Households

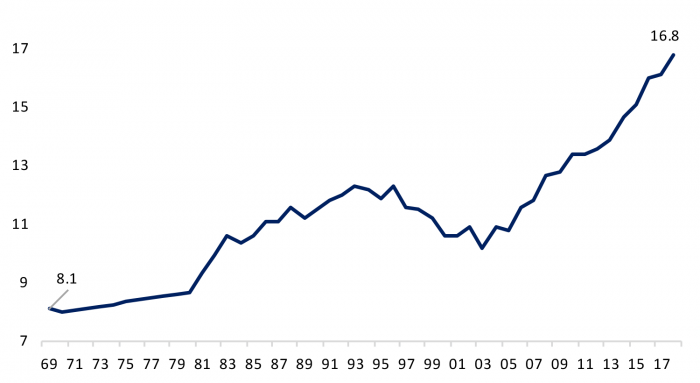

Another pronounced trend among Millennials that has continued despite a robust labor market in recent years is the growing share of multi-generational households. Figure 5 illustrates that the share of 25 to 34-year-old adults living with their parents started rising during the housing boom even before the Great Recession and has continued to make new record highs each year. A recent research paper that looked into the drivers of this trend concluded that the share is even higher than that shown in the chart and stood at 22% in 2017. The paper looked at detailed, household-level data in order to parse how much of the rising trend of young adults living with their parents reflects changing demographics, changes in marriage patterns, rising rents, local economic conditions and the ability to access home ownership due to increased student debt and tighter credit standards. Economics are one key part of the story; people earning less and those living in high-rent cities are more likely to live with their parents, and the largest increases in cohabitation over the past ten years were among those of moderate or low incomes living in high-rent cities. That said, even households earning more than $50,000 per year saw an increase in multigenerational living arrangements.

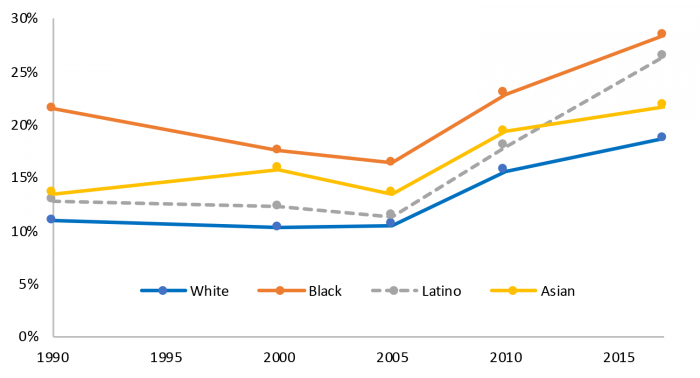

The substantial shift in the demographics of Millennials raises the question as to how much of the change in living arrangements is a matter of culture and preference rather than economic and financial considerations. Figure 5 shows the share of 25 to 34 year olds living with their parents by race and ethnicity. While there is a notable difference across groups, all have seen a substantial increase in recent years. Controlling for income, education and local economic conditions, the authors find no difference in the propensity of black and white young adults to live with their parents, while Asians are 9% more likely to live with their parents and Latinos are 3% more likely. Applying these propensities to the changes in population composition suggests only 10% of the doubled share of 25-34 year olds living with their parents is attributable to changing demographics.

Figure 5: Share of 25-34 Year Olds Living with Their Parents (%)

The authors find that nearly a third of the increase in cohabitation is attributable to later ages of marriage among Millennials. There is of course a great deal of interaction in economic and social trends. Lower earnings and greater job insecurity for a generation coming into the labor force in the aftermath of the Great Recession likely contributed to later marriages, as well as increased student debt. The authors followed individuals aged 25 and 34 over a ten-year period and found that of those who had been living with their parents at the start 68% had formed their own households and 54% had become homeowners ten years later, suggesting that the bulk of cohabitation is a delay in household formation rather than a matter of preference. However, the group studied were members of Generation X and it remains to be seen how Millennials will proceed from here.

Figure 6: Share of 25-34 Year Olds Living with Their Parents (%) by Race and Ethnicity

The Millennial generation still bears perhaps the most lasting scars from the Great Recession. While higher income and older households with significant investments in the stock market or equity in housing have seen a recovery in wealth, Millennials have seen delayed homeownership and have not yet accumulated significant financial assets. Millennials stayed in school longer and enjoy a higher rate of college graduation, but at the cost of accumulating student loan debt that has impeded or delayed their entry into homeownership, and has not enabled them to reap the benefits of higher real wages. The imprint of a more difficult launch into the labor market on social trends of reduced and delayed marriage and fertility has macroeconomic consequences through reduced population growth. There is still time for millennials to enjoy the benefits of rising real wages, particularly if the US manages to avoid a recession in coming years. However, longer life expectancies combined with delayed opportunities for wealth building through home ownership suggest retirement security will be a particular challenge for this generation.