A risky proposal with the potential to harm the intended beneficiaries

The proposed $15 per hour minimum wage will affect the wages of nearly 20% of the full-time workforce in New Jersey. Using the same fundamental assumptions as economists employed by the Congressional Budget Office during the Obama administration in 2014, I calculate that a $15 per hour minimum wage will reduce employment of lower-wage earners in New Jersey by more than 5.5% and will destroy more than 20,000 full-time lower-wage jobs. I discuss how the $15 per hour minimum wage acts like a tax; my calculations suggest that the $15 per hour minimum wage effectively taxes income of workers earning more than $15 per hour — roughly 80% of all workers in New Jersey — an additional 1.5 percentage points. The $15 per hour minimum wage is an extremely risky policy that adds to the tax burden of a high-tax state and likely adversely impacts a large fraction of low-wage workers via negative employment effects. This $15 minimum wage proposal requires extensive debate; it should not be rushed through legislation.

At the end of the day, the proposed $15 per hour minimum wage is just another tax in a high-tax state. Like many taxes, it is not obvious who bears the full cost of the tax. And, unlike some tax and transfer schemes, the $15 minimum wage has the potential to harm a large fraction of its potential beneficiaries.

A $15 per hour minimum wage would affect a very large fraction of the labor market. Using Census data, I compute that roughly 16% of all full-time workers in New Jersey in 2014, the most recent year available, earned less than $15/hour. Once I consider anyone that worked more than 13 weeks per year in 2014, the figure jumps to 22% of all workers.

Consider the following: A law has been proposed that might affect the compensation and employability of roughly 20% of all workers in New Jersey. This law should be subject to due diligence and scrutiny. I am nearly certain that if one were to poll serious economists studying the minimum wage, that very few of these economists would suggest an increase past $12 per hour. The current minimum wage in New Jersey is $8.60 per hour. A $12-per-hour minimum wage would represent nearly a 40% increase.

You might wonder why I call the minimum wage a tax. The reason is that somebody has to pay for the increase in wages. And the potential tax burden is quite large. In 2015, New Jersey had 2.4 million full-time workers defined as working at least 50 weeks and at least 40 hours a week [see Endnotes 1 and 2]. For convenience, split these 2.4 million workers into two groups, Groups A and B. Group A consists of 2 million workers all earning above $15/hour and Group B consists of 400 thousand workers all earning less than $15/hour. Rounding a little, the average wages of workers in Groups A and B are about $41 and $12 per hour, respectively. Now, imagine a scheme that taxes each member of Group A and transfers those taxes to Group B such that after receiving the transfer, each member of Group B earns exactly $15 per hour. In other words, Group A has to pay for the increase in salary given to Group B. On average, each member of Group A has to pay a tax of $0.60 per hour to fully fund the new $15 per hour minimum wage earned by every resident of Group B [see endnote 3]. $0.60 per hour is a 1.5% tax on a baseline hourly wage of $41 per hour. Viewed through the lens of this simple example, the $15 per hour minimum wage would raise the tax rate on labor income an additional 1.5 percentage points for the Group A workers, 84% of full time workers in New Jersey. This is a big increase for a population that already pays some of the highest taxes in the country.

Of course, proponents of the $15 minimum wage argue, correctly, that what I describe is not actually how the minimum wage works. My analysis simply reinforces the point that a minimum wage is a transfer, which acts like a tax on someone. If we pass a law forcing “Group B” workers to be paid a higher wage, this law does not imply that Group B workers will suddenly produce more output per hour and thus justify their higher wage. Rather, someone else in the economy will likely have to accept either less income or purchasing power for workers in Group B to earn more income. This is the essence of a tax-and-transfer scheme.

When mainstream economists describe the possible outcomes of an increase to the minimum wage, they allow for a few scenarios. First, employers can try to pass through the extra labor costs imposed by the new minimum wage in the form of higher prices. If the employer cannot raise prices, then firm profits fall; this is like a tax on owners of firms. This decline in profits might be short lived, as owners of capital demand a certain return given a certain level of risk, suggesting firms will leave the state over time. If firms can, in fact, charge higher prices, then these higher prices are like a tax paid by consumers. Of course, even if firms can raise prices not all consumers are willing to pay higher prices. When prices rise, demand falls – this is the so-called “law of demand” — and the reduction in demand will lead to a reduction in employment. Even absent a decline in product demand, firms can reduce the tax burden of the $15 minimum wage by substituting capital for labor. For example, grocery stores might replace some cashiers with self-service checkout equipment.

Most of the debate among economists about the minimum wage is not about whether or not it is a tax, but whether or not the minimum wage reduces employment for low-wage workers, exactly the set of workers the minimum wage is supposed to help. The profession is unsettled about the size of the impact on employment for changes to the minimum wage. This is a thoroughly researched topic and dedicated scholars using rigorous methods have produced a wide range of estimates, including zero, but the conclusion of most studies suggests some kind of employment loss. Use an estimate from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in its February, 2014 study of the impact on aggregate employment if the national minimum wage were to be increased from $7.25 per hour to $10.10 per hour. The CBO estimate is that a 10% increase in the minimum wage reduces employment for lower-skill workers by about 1% (see p. 25 of this document). Once we apply this estimate to the proposed $15 minimum wage in New Jersey, we should expect to see a reduction of employment for Group B workers of 5.56% [see Endnote 4]. In other words, we should expect approximately 22 thousand fewer full-time Group B workers out of 400 thousand as a direct result of the proposed increase in the minimum wage.

Much of the discussion around the minimum wage centers around fairness, that somehow the gap between low-wage and high-wage workers that is set in the labor market is unconscionably large. It is hard to argue fairness, as what is considered “fair” is an opinion. We know that markets produce inequitable outcomes and sometimes for good reasons. As an example, Tom Brady (quarterback, New England Patriots) makes about $14 million per year and Josh McCown (quarterback, New York Jets) makes about $6 million per year. Is this a fair wage differential? I don’t know. But I think it is safe to say most football fans would rather have Tom Brady at the quarterback position than Josh McCown, and the wage differential between Tom Brady and Josh McCown’s salary reflects this reality.

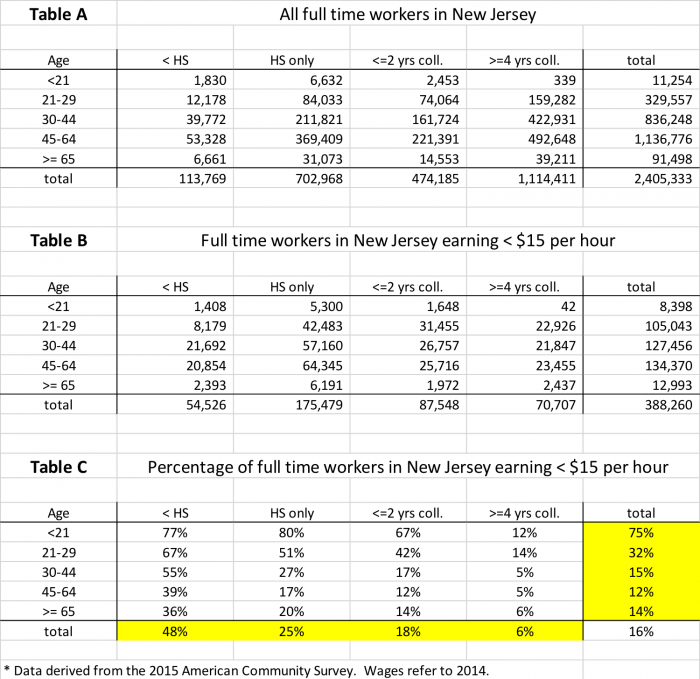

As an attempt to put some perspective on the fairness or lack thereof of the $15 per hour minimum wage, I compute the age and education of all full-time workers in New Jersey, and the full time-workers in New Jersey that currently earn less than $15 per hour. Table A shows all workers in New Jersey; Table B shows the workers earning less than $15 per hour; and Table C shows the percentage of workers in Table A earning less than $15 per hour. The data are sorted by age and by education. The four education categories I consider are workers lacking a high school degree (“<HS”), workers with only a high school degree (“HS only”), workers with up to two years of college (“<= 2 yrs coll.”), and workers with four years of college or more (“>= 4 yrs coll.”). I compute all the statistics in Tables A, B, and C using Census data from 2014, as before.

Based on Tables A, B and C, some broad takeaways for full-time workers in New Jersey are apparent. First, as shown by the highlighted cells in Table C, only 6% of college graduates earn less than $15 per hour. In contrast, 25% of high school graduates and 48% of workers with less than a high-school degree earn less than $15 per hour. Second, 15% or less of workers aged 30 and older earn less than $15 per hour. 32% of workers between the ages of 21 and 30 earn less than $15 per hour and 75% of the small number of full-time workers under 21 earn less than $15 per hour. In conclusion, markets pay older, more educated workers larger wages than younger, less-educated workers; a $15 per hour minimum-wage law targets less-educated and younger workers. There is a sense in which at least some of the wage differential between these groups of workers is justified. More-educated workers bring additional skills to the labor market; older workers bring valuable experience; and labor markets reward skills and experience. Is the market-determined wage differential between these groups of workers “unfair”, and is a $15 minimum wage needed to restore fairness? I am not prepared to make that statement, the same way that I am not prepared to argue that Josh McCown needs a higher salary because Tom Brady earns $14 million per year.

The discussion of fairness in labor markets naturally leads to other philosophical discussions about ethics and labor markets. To start, perhaps there are jobs in our economy paying so little that we don’t want those jobs to exist and the $15 min wage will likely eliminate those jobs. The question arises: What is the appropriate cutoff? Is it $15 per hour? Why not $35 per hour? More to the point, when we eliminate a job, we destroy a transaction between mutually consenting adults. Society destroys transactions between consenting adults in the case of drugs and prostitution; are low-wage jobs in the same category? Second, is it fair to pay a worker with less education and currently making less than $15 per hour the same amount (i.e. $15 per hour) as a worker with more education? A $15 per hour minimum wage law will adversely impact the incentives for acquiring education and self-improvement for some. That is, some workers will not spend costly resources and time acquiring education and training if these efforts do not lead to an expected increase in wages. Are we comfortable engineering these kinds of dis-incentives into our labor markets?

My former colleague Stephen Malpezzi likes to say that government policy creates winners and losers. We have discussed some of the losers from the implementation of a $15 minimum wage: The minimum wage acts like a tax, and therefore whoever pays the tax loses. Workers who currently earn $11 per hour, keep their job and then earn $15 per hour after the law is implemented are potentially winners. But some of the biggest losers will be current lower-wage workers who lose their jobs. As mentioned, my estimates suggest New Jersey will lose about 22 thousand low-wage jobs if the $15 per hour minimum wage passes. The 22 thousand that lose their job, or fail to gain employment, will (1) earn no wage at all and (2) will not accrue labor market experience. This lack of labor market experience will negatively impact future wages – if they can find employment in the future – since the data suggest that experience is compensated by employers in the form of higher wages.

Steve Malpezzi and David Frame were kind enough to read the blog and provide some feedback, and we engaged in an active discussion over email. True to their scholarly roots, Steve and Dave asked me to talk through all the possibilities and cover all the bases. Summarizing: Steve suggested I reference the growing literature studying Seattle’s $15 per hour minimum wage experiment (the verdict is not yet in). Dave mentioned that we should expect people to move into or out of the state if the minimum wage passes, complicating tax and employment analysis. Additionally, the economy is stronger now than in 2014, and a $15 per hour minimum wage might impact fewer workers than my analysis suggests. That said, I am on safe ground suggesting Steve concluded that even if we are unsure of the exact employment effects, passing this large an increase in the minimum wage is simply too risky given the population of workers this law might affect is extremely economically vulnerable.

I also asked Ron Ladell to review the blog, and after my conversations with him I realize it is important to reiterate that we will not add to or “improve” our economy by increasing the minimum wage. Again, this is because Group A workers are essentially being taxed to fund extra payments to Group B workers. The only way the increase in minimum wage will lead to more output in New Jersey is if the current Group B workers will become more productive after the minimum wage increases because their wage has increased [see endnote 5]. Of course this is a possibility, I just view it as unlikely. It is nearly equivalent to saying that if the Jets want Josh McCown to be a better quarterback, they should just pay him more.

In conclusion: The $15 per hour minimum wage proposal is just another tax in New Jersey with the potential to decrease employment for a sizeable group of low-wage workers. The workers we expect to lose their jobs are largely young and less educated, and a reduction in their employment prospects can have long-lasting implications for their future wages and employability. At a minimum, policymakers should study this issue very carefully before proceeding.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: I download the data on workers and wages from IPUMS at usa.ipums.org. I label a worker as “full time” if weeks worked in the previous year was at least 50 (the IPUMS variable wkswork2 = 6) and hours worked per week was at least 40 (IPUMS variable uhrswork >= 40). I compute hourly wage for each person in the survey as the reported yearly wage and salary income (the IPUMS variable incwage) divided by usual hours worked per week times 50. I then drop from the sample and all computations any full-time workers with a computed hourly wage less than $8.25, the minimum wage in 2014, about 6.2% of the sample.

Endnote 2: If we broaden the universe of workers to anyone working more than 13 weeks, New Jersey has 3.66 million workers of which 808 thousand (22%) earn less than $15 per hour. The average hourly wages of Groups A and B in this case are $39.83 and $11.49, respectively.

Endnote 3: Total compensation per hour paid to Group B is 400 thousand times $12 = $4.8 million. If everyone in Group B were to earn $15 per hour, total compensation would have to equal 400 thousand times $15 – $6 million. The gap that needs to be funded by Group A is $1.2 million per hour = $6.0 million less $4.8 million. This $1.2 million gap per hour would be funded by the 2 million workers in Group A. This gives a cost per worker in Group A of $1.2 million divided by 2 million = $0.60 per hour.

Endnote 4: A technical point is that Economists refer in writing to percentages when they technically refer to log changes. A change from a $8.60 minimum wage to a $15 minimum wage is a change of 0.556 log points (=ln 15 – ln 8.60). Note that 0.0556 = 0.556 * 0.1, where 0.10 is the employment elasticity with respect to log changes in the minimum wage.

Endnote 5: (Technical note) Another way output can rise is if the marginal propensity to consume out of income is higher for Group B workers, those receiving income transfers, than Group A workers, those paying for these transfers. I have not computed them, but do not believe these effects to be large since more than 80% of all workers are in Group A and the overall savings rate for all workers is low.