Or will market momentum cool in its own time?

The Fed continued raising interest rates in September, even as the economy continues to run strong and financial markets flirt with new record highs on a range of asset prices. While the Fed’s dual mandates center on achieving stable inflation and full employment, it has a long and complicated relationship with frothy asset prices. Using higher interest rates to prick asset bubbles is still not standard operating procedure, even as the Fed is far less complacent about risks to financial stability than it was before the housing crash. The recently rumored appointment of Nellie Liang to the Federal Reserve Board, who is the founder of the Fed’s financial stability division, raises the question of whether the FOMC is moving toward using interest rates to lean against the tailwind of the economy from rising and possibly unsustainable asset values. The research conducted by Liang and others suggests that leaning against the wind on asset bubbles is a complicated task that is best addressed by using regulation and macroprudential policies to prevent excess leverage from building up as a self-reinforcing but dangerously unsustainable support to financial market momentum. For now private sector leverage in the US does not appear to be surging higher in the aggregate and the Fed will continue marching gradually toward a fed funds rate more in line with its estimate of longer-run equilibrium closer to 3.0%. I expect that a fading boost from tax cuts combined with a clearer bite from trade wars and higher interest rates will combine to cool off market momentum before the Fed needs to lean hard and pull the punch bowl away in a more disruptive manner.

The complicated relationship between the Fed and asset bubbles

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates last week and a December rate hike seems all but a done deal. At the same time Fed Chair Powell remains committed to a gradual pace of tightening, which effectively sets a speed limit of four rate hikes per year. Meanwhile economic growth has continued to run strong, and the stock market continues to flirt with new record highs despite intensifying trade wars and turmoil in a number of emerging market nations.

Observers are being cautious in describing the current buoyant state of US financial market conditions with investment professionals, using terms like “fully priced” or “at the top of historical ranges” to describe asset prices, and Federal Reserve Policy makers are describing valuations as “elevated”. Calling asset bubbles is tricky given the wisdom often ascribed to John Maynard Keynes that “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” For the Fed the assessment is further complicated by the question of what to do even if their best guess is that we are in the midst of a bubble.

The Federal Reserve has a long and complicated relationship with asset bubbles. Prior to the tech boom of the late 1990s business cycles weren’t mainly characterized by booms and busts in asset prices. Post-war business cycles were centered on sustained growth in real economic activity that generated inflationary pressures at the peak of the cycle, prompting the Fed to raise interest rates to cool the economy down. However, inflation has remained persistently low and less cyclical in recent decades and Fed Chair Powell observed in a speech this past August that “the two most recent U.S. recessions stemmed principally from financial imbalances, not high inflation, [highlighting] the importance of closely monitoring financial conditions.”

Before the tech bubble in the stock market of the late 1990s, the Fed’s stated approach was not to opine on asset valuations which were best left to free markets to determine, but to respond to the macroeconomic fallout should an asset bubble burst. This reaction function where the Fed stayed neutral in a boom but helped clean up the mess in a bust was often referred to as the “Greenspan put” because investors knew they had a put option from monetary policy should the stock market decine dramatically.

The Fed’s hands-off approach to financial conditions survived the crash of the tech bubble in the stock market in 2000-2001 and the subsequent rise of the housing bubble of the late 2000s. In the midst of the global financial crisis, whose seeds were sown in the US housing bubble, then Fed Vice Chair Don Kohn gave a soul searching speech titled “Monetary Policy and Asset Prices Revisited” in which he examined whether monetary policy should “lean against the wind” which Kohn defined as policy makers “trying to check speculative activity through tighter monetary policy whenever they perceive a bubble forming.”

Reigning in and monitoring risk taking and financial markets

Instead of being on bubble watch, Kohn concluded that the Fed had fallen short on the regulatory front and should seek to improve their understanding and monitoring of the financial system, including linkages among unregulated and international sectors. In the years that followed the crisis and the passage of the Dodd Frank financial sector reform legislation, the Fed imposed a series of new regulations and financial market reforms that have sought to make the financial system safer. Fed Governor Lael Brainard gave a detailed speech earlier this year on measures taken to date and what is still on the agenda. And Chair Powell included an accounting of these structural improvements in his prepared remarks to the press conference that followed the Fed’s policy announcement last week concluding the financial system is now “stronger and in a far better position to support the financial needs of households and businesses through good times and bad.”

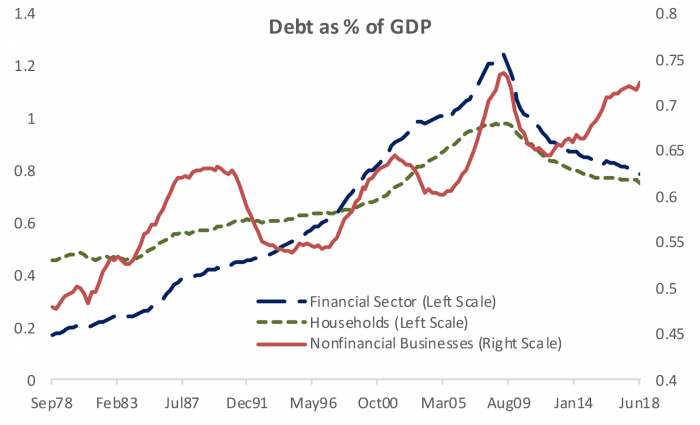

The Federal Reserve Board in Washington also established a new Financial Stability division that briefs the FOMC quarterly with a broad assessment of asset prices, leverage, and maturity transformation in the financial system. The recent report presented to the FOMC in August characterized a broad set of asset prices as currently “elevated with no major asset class exhibiting valuations below their historical midpoints” while vulnerabilities from financial sector leverage and maturity transformation were deemed to be low and risks from household leverage were low to moderate. Aside from asset valuations, the only other potential trouble spot was that “vulnerabilities from leverage in the nonfinancial business sector [were seen] as elevated.”

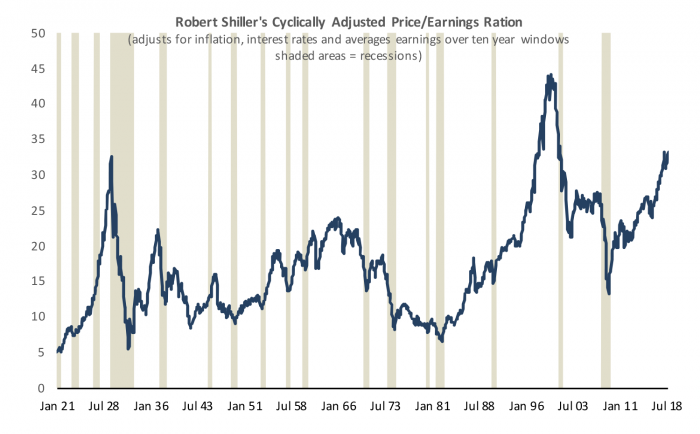

Figure 1 – Equities Appear to be Overvalued by Historical Standards

The financial stability report received by the FOMC in August quietly raised a few red flags from the recent rip-snorting run in markets. In addition, a recent editorial by Nobel Prize winner Robert Shiller argued that current market valuations place too much emphasis on very recent earnings and don’t factor in risks from – among other things – future business cycles, an assessment that is captured in his Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio shown in Figure 1. Martin Feldstein, another prominent economist, has also recently weighed in that the market rally isn’t factoring in the likelihood of rising inflation from a strong economy, and the combination of tighter monetary policy and rising fiscal deficits that should combine to push interest rates higher.

FOMC participants have been nervously eyeing the continuation of buoyant financial conditions with a growing number citing easy financial conditions as a reason to keep raising interest rates above levels seen as consistent with longer-run neutral rates. These remarks, combined with the potential nomination of economist Nellie Liang currently of the Brookings Institution but formerly the founding Director of the Fed’s Financial Stability Division, have raised the question as to whether the Fed is now more inclined to lean against the wind with monetary policy. A careful read of Liang’s extensive research on the subject, along with that of other scholars, suggests the Fed will likely continue to be very cautious in using monetary policy to pop asset bubbles.

What the research says about leaning against the wind of asset bubbles with monetary policy

Just under a year ago, Nellie Liang nicely summarized the recent and growing body of research that explores the link between asset prices and business cycles in “Rethinking Financial Stability and Macroprudential Policy”. Using data across countries and cycles she and other researchers found a tradeoff between financial conditions and GDP growth, with loose conditions boosting growth in the near term but contributing to lower growth outcomes in the medium term, particularly when loose financial conditions are accompanied by excess credit growth (defined as credit growth in excess of GDP growth and recent trends). Traditional economic forecasting models focus on near-term outcomes and systematically underestimate the risks of financial excesses over time. They find that looser financial conditions tend to predict downside risks to growth one year ahead.

Figure 2 – Debt Growth Subdued in the Household and Financial Sectors, Elevated and Rising in the Business Sector

There is growing literature that finds risk appetite to be pro-cyclical. The authors refute the idea that risk taking and growth are supported by the same causal factors (positively or negatively). Instead, the authors found a self-reinforcing and cyclical dynamic causal effect from risk taking and leverage to growth with booms sowing the seeds of downside risks. The authors don’t find that booms and busts even out over the cycle though; busts are costly, particularly when accompanied by excess leverage. One of the more worrying findings is that tightening monetary policy seems to be ineffective in credit booms, or the magnitude of interest rate hikes required to have a meaningful impact on financial conditions might also have an unacceptably high cost in terms of higher unemployment and lower inflation.

The one clear conclusion from the research is that it is desirable to prevent excess credit states of the economy before asset bubbles form through macroprudential policy, defined as financial regulation that varies over time depending on the state of the business cycle. Examples of macroprudential policy include mortgage standards that tighten as housing markets heat up, or counter cyclical capital buffers that require banks to add capital at the peak of the cycle as a sort of rainy-day fund to boost capital when losses rise. The problem for the US is that macroprudential tools for reigning in credit are limited, aside from the various structural enhancements put in place since the financial crisis. The Fed has the ability to impose a counter-cyclical capital buffer at banks, but the effectiveness of raising the counter-cyclical capital buffer in reigning in excess business credit growth may be limited by the fact that most speculative leverage is being extended outside the banking sector.

Household and financial sector leverage in the US do not look particularly excessive, nor do they look to be moving into speculative territory (Figure 2). Business borrowing is moving higher, suggesting risks that firms are getting credit that will prove unsustainable and serve as an accelerator in the next downturn as defaults of untenable businesses rise, forcing layoffs and cutbacks in investment. For now the Fed is proceeding gradually toward a Fed funds rate more in line with estimated longer-run neutral interest rates closer to 3.0%. Harder questions for monetary policy await in mid-2019, and we suspect that fading boosts to corporate earnings from tax cuts combined with a growing bite from trade wars may combine to cool off some of the speculative momentum in the asset prices and lead the Fed to slow its pace of rate hikes in search of a soft landing for the US economy.