Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) pulls up a chair

The US and other advanced economies have seen steadily rising government deficits and debt as a percent of GDP in recent decades, a development that no mainstream economic theory would predict is an optimal development. Yet even as federal borrowing rises, the politics and economic thinking about deficits has been evolving toward a growing consensus that rising deficits may not be as much of a problem as previously believed. The shift in economic thinking has been in part a sensible reaction to changes in the macroeconomy and recent experience with persistently low interest rates and limited repercussions from rising deficits. Another less mainstream theory that has been gaining traction in progressive political circles, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) holds that deficits don’t matter at all. While the belief that deficits may not be as harmful as previously believed is supported by the data to date, there is a risk that past isn’t prologue. Reliance on foreign funding and global capital markets combined with changing demographics point to some risk that ever rising debt could become destabilizing at some point, and will almost certainly channel resources away from private investment at some greater or lesser cost to growth potential.

A Brief History of the Politics of Federal Debt in the US

The history of government debt in the US goes back to when the Continental Congress authorized the issuance of notes to European investors and wealthy colonists in order to finance the Revolutionary War. In the aftermath of the war, Alexander Hamilton spearheaded the effort to consolidate the debt of various states that had also borrowed during wartime to the federal level in order to alleviate the economic burden on our young country and establish the creditworthiness of the United States government. Over the history of this country the federal deficit has fluctuated between surplus and deficit with borrowing used to finance wars and territorial expansion. Deficits have historically been unpopular across political parties and viewed as a last resort in times of difficulty. Hamilton recognized the importance of establishing the credibility of the dollar and creditworthiness of the US government so that the option to borrow from investors in times of need would be available.

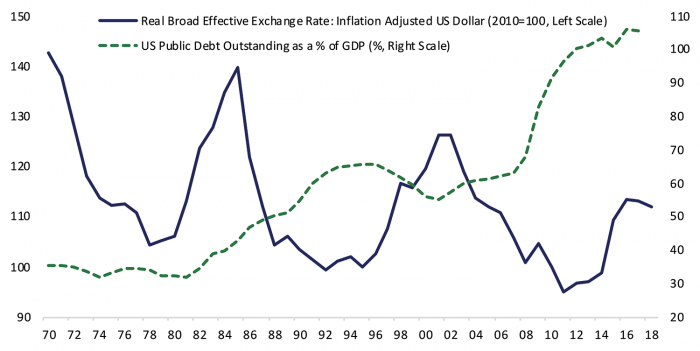

Figure 1: The Real Value of the Dollar Has Been Largely Unaffected by Rising Federal Debt

As the US economy and the dollar became dominant after World War II the concern about maintaining creditworthiness was less of a focus and federal deficits became the norm. Over time the dollar came to be seen as overvalued in part reflecting deficit spending in the 1960s and the post-war Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates against the dollar which was dissolved in the early 1970s. The real value of the dollar declined steadily through the 1970s and the US saw a period of stagflation, a combination of low growth and high inflation. Some Republicans and Democrats called for a balanced budget amendment to the US constitution during this period. Although the US never came close to passing such an amendment, and indeed the 1980s saw a return to rising federal deficits, most states have some form of balanced budget requirement.

In recent years the Republican party has ostensibly been the party of fiscal discipline, although in practice the divide between Republicans and Democrats has less to do with actual policies and more to do with what each party believes deficits should be spent on. This was brought into sharp relief in the past two years as many of the same Republican legislators who shut the government down and brought about a downgrade of the credit rating of the US in 2011 by refusing to raise the debt ceiling and threatening a default turned around and passed a massive tax cut with resulting projections of deficits above a trillion dollars in perpetuity.

The Economics of Public Debt

Like the mainstream political view, economic textbooks tend to view government deficits as appropriate primarily in the case of economic distress. Both classical and Keynsian economists generally agree that deficits can be useful when the economy is in recession and the federal government can help jump start demand when the private sector is pulling back. In addition, it is recognized in mainstream macroeconomics that certain intergenerational transfers may be welfare enhancing for the population as a whole and require a certain amount of deficit financing. However, sustained deficits and rising debt levels are predicted to lead to rising interest rates that will in turn crowd out more productive private investment, thereby lowering the growth potential of the economy over the long run.

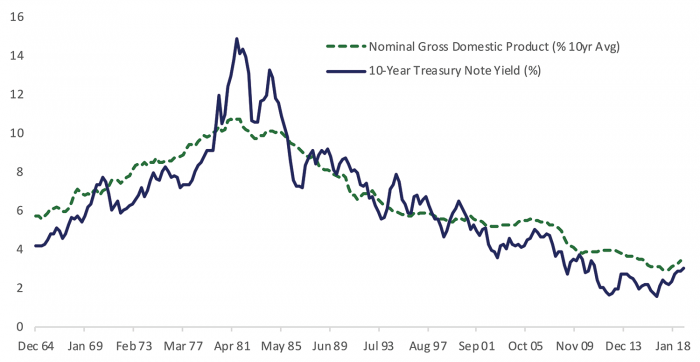

Figure 2: Long-Term Interest Rates Have Mostly Been Below Nominal Growth Rates

More recently, however, even orthodox macroeconomists have started to question whether deficits are so bad after all. MIT professor and former Chief Economist of the IMF, Olivier Blanchard, delivered his presidential address to the American Economic Association this past January laying out a detailed argument for why public deficits may not be so bad after all. The crux of his argument is that interest rates have been persistently low, and importantly lower than the nominal growth rate of the economy. Indeed, as we have pointed out in prior posts, yields on 10-year Treasuries have generally been below the economy’s growth rate for much of history, excluding the 1980s and early 1990s (Figure 2). Blanchard notes that if debt can be rolled over and the interest can be paid out of economic growth then there is no future fiscal cost to a current deficit. Blanchard acknowledges that even with low interest rates there is a potential welfare cost to public borrowing as it reduces the capital available for private borrowing and investment. However, he notes that the welfare cost depends on the relative returns to private and public investment, and that if the return on private capital isn’t that much higher than public investment the welfare cost may be fairly low. Blanchard also notes that while the cost of running a given deficit may be low when interest rates are below growth rates, there are risks from perpetual deficits and rising debt levels.

An Alternative School of Thought

Blanchard makes no mention in his treatise of a school of economic thought that has been gaining traction of late, but one that has long argued that the cost of public deficits and debts is much lower than commonly perceived. Modern Money Theory (MMT) puts government borrowing in an economy wide accounting framework. If the government borrows money, the person lending the money receives an asset in the form of a bond. The government controls how much money is circulating in the economy and proponents of MMT point out that government taxation and spending simply moves that money around.[1]

Although MMT has been associated with progressive politicians like Bernie Sanders, many of its underpinnings are actually fairly orthodox. Proponents of MMT, like classical and Keynsian economists, believe that the economy’s growth potential is mainly an organic function of its people, capital, and natural resources. However, they believe that the government should set spending to achieve full employment regardless of the resulting deficit. MMT believes monetary policy should help finance deficits with quantitative easing in order to keep interest rates low so long as there is no inflation, which there shouldn’t be if the economy isn’t at full employment (MMT also assumes that interest rates are primarily driven by expectations of Fed policy and inflation, an assumption I will return to later). The theory has gained traction in the aftermath of the Great Recession when growth has been frustratingly low and interest rates and inflation remain low and stable.

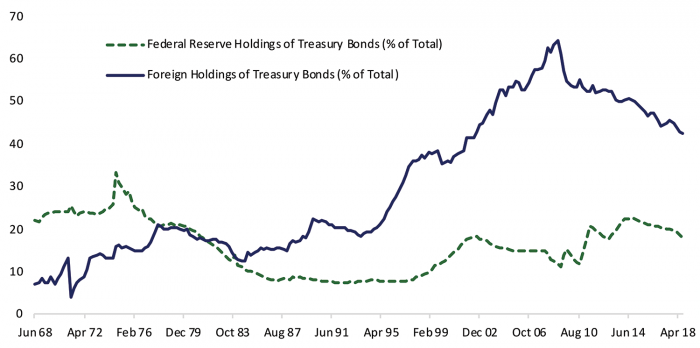

Figure 3: The US Relies Heavily on Foreign Investors to Fund Deficits

The main difference between traditional macroeconomists and proponents of MMT is the institution responsible for maintaining full employment and price stability. For traditional macroeconomists that is the independent central bank who will do what is best for the economy free of political influence. Proponents of MMT argue that the central bank’s tools are limited, particularly in a low-growth aging economy, and the federal government has more powerful, direct means of influencing the economy through taxes, transfers, spending and public investment.[2] Existing automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance are exactly what MMT proponents have in mind as an appropriate cyclical role for fiscal policy, although they advocate for a much more aggressive fiscal stance including a federal jobs guaranty so that the economy never realizes a shortfall from full employment.

Markets and the Global Economy Will Determine How and When Deficits Matter

Perhaps the most important shortcoming of both MMT and orthodox macroeconomics is they lack a central role for global capital markets. Blanchard acknowledges the risk that there might be two equilibria, one in which debt rises but interest rates remain low and stable and another in which investors lose confidence and a country enters a debt-induced death spiral in which higher rates increase debt burdens and a country eventually defaults. This is not a theoretical concept. Argentina has experienced such a death spiral in recent years and loss of confidence in Greece’s ability to service its debt nearly brought the European Union to its knees twice in the past decade. Nonetheless, Blanchard’s recent sanguine view on debt and proponents of MMT take the value and stability of the currency as given and look at the economy mostly from a closed, domestic standpoint.

Figure 3 shows that the US is reliant on foreign investors to fund the deficit. Foreign entities held a peak of 64% of marketable Treasury outstanding as of 2008, but that has fallen to 42% in 2018. The Fed has indeed stepped in and effectively helped finance increased federal borrowing at a lower cost in the aftermath of the Great Recession, although they are now net sellers of federal debt.

There was concern at the beginning of last year that the deficits initiated with the recent tax cuts would lead interest rates to rise in order to induce investors to fund the additional borrowing, and interest rates on 10-year Treasuries have indeed risen from closer to 2% in recent years to just below 3% over the past year. However, domestic institutional investors and households have stepped in to finance the borrowing at these higher rates, the value of the dollar is strong and stable, and the economy continues to hum along for now. Importantly, inflation has also remained low and stable suggesting we are not presently at risk of stretching resource utilization and overheating the economy. The conclusion that higher deficits may come at a relatively low cost seems to hold for now.

A potentially worrying perspective blending economics with political economy comes from Pierre Yared at Columbia University. Yared points out that economic theory can’t really explain the trend across advanced economies towards ever rising debt to GDP ratios, particularly as these rising debt burdens are occurring outside wars and recessions. He turns to political economy and suggests that aging populations give rise to powerful older voting blocks who value their current well-being over that of future generations. If we again bring in the capital markets perspective, we can see that older populations can lead to both demands for higher deficit spending and more conservative portfolio allocation toward bonds and greater financial repression from the regulation and the central bank. The equilibrium might be high deficits and low interest rates in contrast to predictions of traditional economic models. Japan is a good case in point, and a country where the lines between fiscal and monetary policy have blurred over time along the lines suggested by MMT.

Yared also documents a trend towards rising political polarization in advanced economies, which in turn comes with rising turnover between different parties with dramatically different priorities such that each party seeks to put their agenda in place quickly and tie the hands of future governments before the political pendulum swings away from them. These parties are behaving rationally and seeking to fulfill the demands of their voters, but the result is ever rising debt.

For MMT proponents rising debt levels in advanced economies probably aren’t seen as a problem given that inflation is also low, and it is understandable that progressive politicians want their turn in taking advantage of the current environment of low interest rates to implement their agenda. But Yared’s perspective highlights the shortcomings of relying on fiscal authorities to do the responsible thing if inflation or interest rates were to begin to rise. Given the current institutional arrangements in the US, the Federal Reserve would be forced into either making the difficult decision the Volker Fed made in the 1980s in the case of high inflation, or engaging in Quantitative Easing again in the case of higher interest rates (much as the Bank of Japan has had to do). The higher debt to GDP rises, the greater the likelihood of Blanchard’s bad equilibrium and a fiscal crisis if debt burdens cross a threshold that investors see as unsustainable. We have already experienced financial crises in Europe in recent years and recent Italian political developments suggests a possibility we may see another crisis at some point. The US enjoys a strong position as the world’s reserve currency, a status that is unlikely to be upended any time soon by China or cryptocurrencies. Nonetheless, in contrast to Japan, the US is more subject to the mood of foreign investors and global capital markets, and the current status quo can’t be presumed to hold forever regardless of debt levels. Deficits and debt may not matter until they matter a lot.

[1] A leader of MMT is Stephanie Kelton, a professor at State University of New York at Stony Brook who wrote an op=ed in the New York Times titled “How We Think About the Deficit Is Mostly Wrong” in 2017.

[2] A good comparison of traditional macroeconomics and MMT was written by Arjun Jayadev and J.W. Mason titled “Mainstream Macroeconomics and Modern Monetary Theory: What Really Divides Them?” in 2018.