Mortgage markets that function. Or not. Global perspectives, part I

“Cities are built the way they are financed,” according to Bertrand Renaud, the doyen of global housing finance analysts. The stalled apartment construction site from an unnamed African city in Exhibit 1* is a graphic illustration of this principle.

Exhibit 1

When I started the international phase of my career at the World Bank in the early 1980s, I had the privilege of learning from great professionals both at the Bank and especially in-country from my trips to Africa, Asia and the Middle East. They were far too numerous to thank by name. My early travels and tutelage taught me that the best empirical economics sometimes comes not from running regressions on large databases or solving equations (still beloved and illuminating activities!) but from carefully looking around and listening. The noted social scientist Lawrence Peter Berra was correct when he reminded us that “you can observe a lot just by watching.”

Among those lessons: If I drove around a new city and spotted numerous stalled apartment projects in a place that I was invited to discuss housing shortages. Or if I noticed a number of one- or two-story houses lacking finish but designed to support another story (or two), with slowly growing piles of bricks and rebar on the roof. I concluded that I was almost certainly in a place where the housing finance system was grossly underperforming. The regression equations and balance-sheet analyses that came later would confirm what the naked eye had already divined.

Why do unfinished buildings and piles of bricks serve as red flags for dysfunctional mortgage markets and other finance? In countries with well-developed mortgage markets, many households are able to purchase a house today, more or less suitable to their needs, with some partial down payment, and pay off the rest over time. Absent a mortgage market, that purchase and the benefits that flow from it are seriously delayed. Furthermore, in a country with a highly disrupted financial system – think bank deposit rates of 6 percent while inflation is running 20 or 30 percent – saving in a bank account is a fool’s errand. One “saves” outside the financial system, by buying bricks or rebar with any spare cash, and storing them on the roof, until you’ve acquired enough material to add a room or floor.

A few weeks ago we started our examination of mortgages with a look at the evolution of the U.S. housing finance system. Before we dive into the details of mortgage markets around the world (including the U.S., of course), some preliminaries. First we’ll review exactly why mortgages, and finance in general, are so important. Then we’ll remind ourselves just how different the economies and housing markets of different countries can be. It’s this variation, combined with variation in the institutions and practices in different mortgage markets, that allow us to draw powerful lessons from international comparisons.

In future posts we’ll examine some international differences in the underlying asset, focusing on housing prices. Then we’ll examine differences in mortgage markets, including the design of mortgage instruments (for example, fixed or adjustable rate? short or long duration? recourse to other assets in default, or not?) and how mortgages are funded (for example, banks and other depository institutions? securitization? covered bonds?). Finally, we’ll examine outcomes across countries, including both the depth of the mortgage market, and tests for effects of mortgage conditions on homeownership rates.

Back to Basics: What Is Financial Intermediation? Why is it Especially Important for Real Estate?

Without finance, the only agents (firms or households) who can invest are the very same agents that save beforehand. If you have a great investment idea but haven’t saved, tough luck. If you’ve saved but don’t happen to have a great investment opportunity yourself, too bad.

Intermediation is the most fundamental function of finance – different agents can save, and invest; finance then matches the two kinds of agents. Intermediation can also occur in other, non-financial ways, e.g. through well-developed rental markets, as will be discussed further below.

The classic example of financial intermediation used in class involves education. Middle-aged people like the (ahem) older instructors typically make more money than they spend. (It’s conceivable if the instructor’s children have themselves finished college.) Older instructors have a comparative advantage in saving. But we may not have great personal investment opportunities that make our savings grow. I’ve spent a lot of years in school already, I don’t need to buy a house, I haven’t got any great ideas for a start-up this week. But if I put my savings in the bank or a 401(k), the financial system will find those better investors; the bank and I will share the returns.

Young people like the students in the class don’t make much money (yet) but need to spend money on rent, food – and tuition, and books. They have a great investment opportunity, namely their future. So they borrow from a bank (financial intermediation) and/or rely on family funds (non-financial intermediation).

Finance permits the separation of saving and investing. Some agents have a comparative advantage in saving. Other agents have a comparative advantage in investing. The financial system matches us up, to the benefit of both parties.

Finance also helps in price discovery, especially of discount rates: how much we value a dollar today versus a dollar in the future. Time is money!

Finance helps intermediate between short-run savers, investors, and those with a longer time horizon. This borrowing short and lending long gives us a term structure, or yield curve, as Julia Coronado explained to us a few weeks ago.

Finance helps measure and puts a price on risks (outcomes with analyzable probabilities) and sometimes on uncertainty (when we don’t know much about the probabilities of different outcomes). Financial instruments that allow us to bet on unknown outcomes are sometimes called contingent claims.

Financial instruments can be traded, often more easily than the underlying assets themselves. This can provide liquidity and stability to a market.

Unfortunately, finance can, under certain circumstances, be destabilizing instead of stabilizing. In extreme cases such instability can develop into financial crises that can be very bad for an economy, as the events of the mid and late 2000s remind us. Such problems are more likely to arise when there’s a disconnect between the underlying assets and the financial instruments. Can you say synthetic CDO squared? Risks are also higher when markets are opaque – e.g., there’s a lot of counterparty risk; or even worse, when there is uncertainty about who the counterparties are, as in the Lehman Brothers and AIG episodes in 2008.

So finance is fundamental to any healthy growing economy, and finance gone wrong can bring an economy down. Why is it so important to real estate markets? First and foremost, because real estate, residential and non-residential, comprises such a big chunk of the economy – circa 70 percent of the tangible capital stock! – with a very long life – decades for buildings, centuries or more for land.

Furthermore, real estate is ubiquitous. Everyone needs a place to live, every firm needs offices, factories, stores, infrastructure. Everybody needs to invest in this large, long-lived asset. Without mortgages, you can’t buy your house or office or factory until after you save the money. In the absence of finance, options for most agents would be limited. Agents could wait a long time until they save enough; which would retard capital formation and cause good investment opportunities to be lost. Or one could rent, which is itself a form of intermediation. Renting has its advantages but also exposes agents to certain risks, for example nonrenewal of leases and rent inflation.

Why is renting a form of intermediation? Landlords are agents that have an asset (an apartment or an office) that they don’t have a good personal use for. Potential renters have a good use but lack the capital (or have some other reason not to buy). A good rental market works in many respects like a good financial market, matching “savers” (landlords) and “investors” (tenants).

But wait! Even landlords are usually people who are good at deploying a certain kind of capital (real estate) but themselves need financing. Some countries focus their housing finance systems on homeowners to the exclusion of landlords. And sometimes to the exclusion of commercial real estate in general. These can be costly mistakes.

To sum up, given the fundamental benefits of finance, it’s no wonder that there is substantial evidence that developed financial markets, including mortgage markets, support economic growth and development. See Fry, Levine, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine Conan Levine and many others; the recent volume on the topic by Yale’s Will Goetzmann is an intellectual tour de force. But it appears we can also have too much of a good thing, as Cecchetti and Kharroubi, Law and Singh, and Arcand, Berkes and Panizza have shown.

Why Look at Other Countries?

Why indeed? Not just to learn about other countries – although that’s a good thing – but also to learn more about our own country, by thinking more deeply about why and how we do things. “One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things,” as novelist Henry Miller put it.

Another example from early in my career illustrates the point. In the 1980s I was part of a team assisting Jamaica with analyses of their housing and mortgage markets. I was eager to read anything I could in preparation for my first trip, and so I devoured an American consultant’s report recommending changes to Jamaica’s housing finance system. The focus of the report was the consultant’s belief that Jamaica lacked a secondary market. The consultant argued a top priority was to create a secondary market institution modeled on Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac to fill that gap.

Hmmm. That made me think, why did the U.S. have Fannie (and later Freddie) to begin with? Well, because we had many thousands of small banks and thrifts (S&Ls, mutual savings banks) that, under America’s unitary banking laws of much of the 20th century, were borrowing and lending to essentially the same people (go re-watch It’s a Wonderful Life); they were extremely undiversified. Furthermore, the fast-growing cities and states in the West needed more mortgage money than their deposit base could provide. More mature locations in the Northeast and Midwest had lots of deposits, comparatively speaking, but fewer opportunities to make good loans. Fannie and Freddie were able to largely solve this problem of geographic mismatch.

Jamaica, on the other hand, had a population of about 2 million at the time; the island is smaller in area than Connecticut. Geographic mismatch was not much of a problem.

I also learned that there was more than one way to solve geographical mismatch, when it occurs. Canada – larger than the U.S. geographically – had solved their geographic mismatch differently: instead of thousands of banks and thousands of thrifts, Canadians took most of their mortgage loans from one of five large banks that spanned the country.

From my Jamaican teachers I learned that before they needed to start thinking about geographic mismatch, they faced other problems like low fixed rates for savers and borrowers, while inflation was then running on the order of 20 percent. Macroeconomic reforms and more appropriate designs for their mortgage instruments were higher priorities at the time than copying Fannie or Freddie.

I learned a lot about Jamaica from that exercise, but it’s also true I learned a lot about the United States. I began to see our system not as a set of institutions that would work anywhere but as a set of institutions designed to solve particular problems in a particular setting. You begin to realize that if you only know one way to solve a financial or economic problem you may not yet know very much about either the problem or the solutions. That’s as true for mortgages and real estate finance as for anything.

All Countries are Different, All Countries are the Same

There are about 200 countries in the world. “About” because once you try to nail down an exact number you’ll find a number of places where the definition of a country is slippery, or disputed. No matter, let’s start with a few that demonstrate how different country economies can perform.

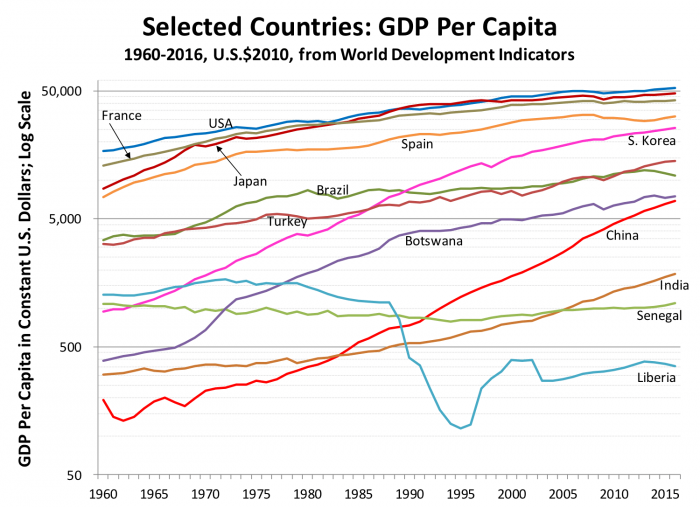

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 2 illustrates something we all know already. Countries vary a lot in their level of economic development, and the path they have taken to get here. We use gross domestic product per capita, adjusted for inflation (in constant $2010), as our basic metric.

In Exhibit 2 the vertical axis is logarithmic. That means, as you’ll remember from high school, the slope of the 12 country lines reveal the growth rates of the variable; i.e., real GDP per capita. Major gridlines – the solid black horizontal lines – represent orders of magnitude of GDP per capita: $50, $500, $5000, and $50,000. The light dotted lines in between the major axes mark increasing values of the dollar amounts between major gridlines. For example, the very bottom line represents $50 per capita GDP; then eight light dotted lines between $50 and $500 represent $50 increments. Notice the minor gridlines get closer together as the underlying variable increases. Then the next major grid line resets at the next order of magnitude, $500, followed by eight minor gridlines at $500 increments until we hit $5,000. Then eight minor gridlines at $5,000 increments until we hit $50,000. Simple, once you get used to it. Readers of a certain age will be thinking, “Hey, that reminds me of my slide rule!” Exactly!

The dozen countries in Exhibit 2 were chosen, non-randomly, to illustrate how different some rich countries are today from some poor countries, but also the limitations of lumping countries into two or three categories like quote “rich and poor,” or “low income, middle income and developed,” or any other simplistic taxonomies we all fall prey to at one time or another. Remember BRICS? Or PIIGS? How about NONSENSE?

Consider just two countries in Exhibit 2, Botswana and Liberia. Both would normally be classified as “developing countries” and both happen to be in sub-Saharan Africa. Botswana started off at about $400 per capita GDP in 1960, then grew rapidly over the next 55 years to about $7,500. Over the nearly 6 decades seen here Botswana’s annual growth averaged 5.4 percent, one of the highest growth rates among all 200 countries. Liberia, on the other hand, started off at $1,300; but after total collapse during its civil war is now at $400, a “growth” rate of –2 percent per year. In what way does it make sense to lump these countries together?

In the event, over the almost 6 decades represented here, the U.S. was more or less at the top of the per capita GDP heap. U.S. GDP per capita in 1960 was about $17,000 in constant $2010. 56 years later it had risen to about $52,000 in $2010. That’s a growth rate of about 2 percent per year over 5½ decades. As it happens 2 percent is also very close to the average growth rate you’ll find over the 140 countries or so for which we have data.

In 1960 France and Japan were still recovering from World War II’s devastation, although both had already made up much of the ground they had lost. France’s 1960 GDP per capita was about $13,000, and Japan’s about $9,000. By 2016 they hit about $42,000 and $48,000 for France and Japan respectively. France’s growth rate was just a shade over the U.S. at 2.1 percent; while Japan’s was a more impressive 3.1 percent despite the lost decades after the bursting of the so-called bubble economy.

Some of the “developing” countries in the 1960s took the “ing” part of the label seriously, and moved ahead as South Korea, China and Botswana illustrate. Korea is especially interesting because as a country with relatively few resources, and the fact that most industrial capacity was in the severed North, half a century ago many “experts” considered South Korea’s prospects as poor at best. So much for experts!

China of course is in many respects the standout story of postwar economic development, not just because of its rapid growth, but also its size and its extraordinary structural changes: it changed from a centrally planned agrarian economy to a rapidly urbanizing market-oriented economy, albeit one still under an authoritarian communist political regime. 1960 Chinese GDP per capita was under $200 and actually fell in the early 1960s as China suffered the effects of the so-called Great Leap Forward. But 50 years later China, while still a poor country, compared to the United States or Europe or Japan has reached a GDP per capita of about $7,000 in $2010. China, as well as other “developing” countries, would appear somewhat closer to the U.S. if we made adjustments for so-called purchasing power parity, which is the price levels of non-tradable goods, in particular the price of housing. By any measure, China’s economic performance has been impressive, including the performance of its housing and other real estate markets. For example, in the decade or so following China’s 1998 housing reform (two decades after the start of economic reform!), floor space per capita consumed by urban Chinese doubled, an achievement unmatched before or since. Joyce Man tells the story well, and Yongheng Deng explains the role a developing housing finance system played.

Given time and space, we could say a lot more about data like that in Exhibit 2. We could examine a few smaller economies that are much richer by this measure than the U.S., like Singapore or Liechtenstein. We could elaborate on the shortcomings of real GDP per capita as a measure – which goods and services do we leave out, like leisure, home production, or many environmental conditions? How is it distributed among individuals? Nevertheless, real GDP per capita is a good place to start when comparing country economies. Readers interested in more data and discussion of differences in growth and development across countries can click here, or see some of the rich debates carried out in works by Deaton, Acemoglu and Robinson, Easterly, and many others.

More to Come

Now that we have some preliminaries about national economies and finance under our belts, we’re ready for future posts. In Post II of this series, in a few weeks, we’ll examine some international differences in the underlying asset, focusing on housing prices. Then we’ll examine differences in mortgage markets, including the design of mortgage instruments and how mortgages are funded. In Part III, in June, we’ll examine outcomes across countries, including both the depth of the mortgage market, and tests for effects of mortgage conditions on homeownership rates.

* Licensed from Shutterstock

Sources, and Further Reading

Acemoglu, Daron, and James Robinson. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Books, 2012.

Arcand, Jean Louis, Enrico Berkes, and Ugo Panizza. “Too Much Finance?” Journal of Economic Growth 20, no. 2 (2015): 105-48.

Brazys, Samuel, and Niamh Hardiman. “From ‘Tiger’to ‘Piigs’: Ireland and the Use of Heuristics in Comparative Political Economy.” European Journal of Political Research 54, no. 1 (2015): 23-42.

Buckley, Robert M, and Jerry Kalarickal. Thirty Years of World Bank Shelter Lending: What Have We Learned? World Bank Publications, 2006.

Cecchetti, Stephen G, and Enisse Kharroubi. “Reassessing the Impact of Finance on Growth.” (2012).

Cerutti, Eugenio, Jihad Dagher, and Giovanni Dell’Ariccia. “Housing Finance and Real-Estate Booms: A Cross-Country Perspective.” Journal of Housing Economics (2017).

Deaton, Angus. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Demirgüç-Kunt, Aslı, and Ross Levine. Financial Structure and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Comparison of Banks, Markets, and Development. MIT press, 2004.

Deng, Yongheng, and Peng Fei. “The Emerging Mortgage Markets in China.” In Mortgage Markets Worldwide, edited by Danny Ben-Shahar, Charles Ka Yui Leung and Seow Eng Ong, 1-33: Blackwell, 2008.

Easterly, William. The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. MIT press, 2001.

Fry, Maxwell J. Money, Interest, and Banking in Economic Development. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.

Goetzmann, William N. Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible. Princeton University Press, 2016.

Law, Siong Hook, and Nirvikar Singh. “Does Too Much Finance Harm Economic Growth?”. Journal of Banking & Finance 41 (2014): 36-44.

Levine, Ross. “Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda.” Journal of economic literature 35, no. 2 (1997): 688-726.

Litan, Robert E. “In Defense of Much, but Not All, Financial Innovation.” 2010.

Man, Joyce Yanyun. China’s Housing Reform and Outcomes. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge, MA, 2011.

O’Neill, Jim. “Building Better Global Economic Brics.” (2001).

Rajan, Raghuram G. Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. Princeton University Press, 2010.

Reinhart, Carmen M, and Kenneth Rogoff. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Renaud, Bertrand. “Housing and Financial Institutions in Developing Countries.” World Bank Staff Working Paper 658 (1984).