Low income housing programs that work: Part 3

This is the third of three blog posts focusing on the role of Housing Choice Vouchers in assisting low-income households that face housing “affordability” problems. In our first post we focused on the cost effectiveness and the transfer efficiency of vouchers; that is, how much bang for the taxpayer’s buck we get when we examine how much it costs the government to deliver a good or service compared to its market value, and how recipients value housing vouchers compared to public housing and other so-called supply-side housing programs. We found that vouchers clearly outperformed the competition by these metrics.

In the second post we focused on the broader question of possible market effects of housing vouchers, and compared them to the market effects of supply-side subsidies. We discovered that – to the extent there is responsiveness of housing markets – the empirical evidence suggests that even a large voucher program would have modest, if any, effects on rents, and that large voucher programs could increase the overall stock of housing. Furthermore, even if supply is inelastic, it’s still an open question about which is most cost-efficient. After all, public developers, or public-private partnerships as in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, must still face high land and development costs, and resistance to development from NIMBYs.

In other posts we discovered that some common solutions to the affordability problem, including rent control and inclusionary zoning, were unlikely to work well.

This post will be a little more au courant, at times a bit forward looking. We will focus on several recent developments in the Housing Choice Voucher program, including but not limited to budgetary issues, and some important proposals for changes and/or reform.

After this post, we’ll take a break from vouchers, although we have not exhausted all the issues. For example, in a future post we could say much more about the non-pecuniary effects of vouchers on welfare, e.g. on child development and health (Newman and Halupka); on how vouchers can affect household mobility, and why this matters (Turner and Popkin); and how vouchers, and other low-income housing programs, affect neighbors (Davis, Gregory, Hartley and Tan). Instead, in a few weeks we will focus on the other element of our two-pronged housing strategy: reform of land use and development regulations that can improve the responsiveness for the market across the board, for households of all incomes and compositions.

HUD Expenditures on Low-Income Housing: Past, Present and Future

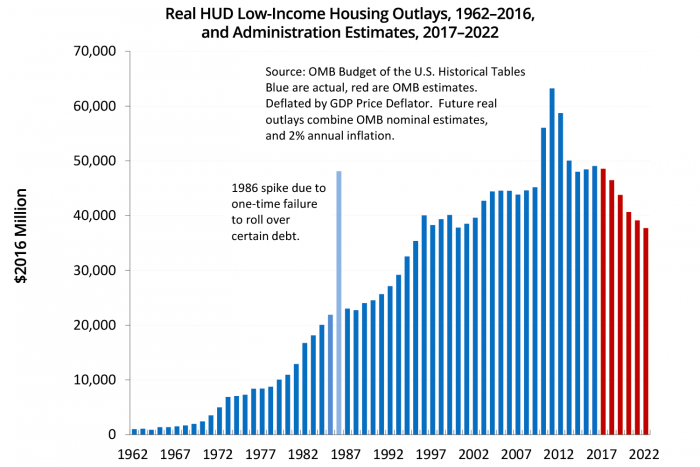

Exhibit 1 presents overall data on HUD’s overall spending on low-income housing, including both supply-side and demand-side programs. The smaller tax expenditures on Low-Income Housing Tax Credit units, and still smaller USDA programs for rural areas, are omitted. And, of course, the much larger mortgage interest deduction and deduction for property taxes, not directly relevant to many low-income households, are also omitted.

Focus for the moment on the blue bars, only, in Exhibit 1. These are actual annual outlays, in millions of inflation-adjusted dollars, through 2016. While there are some ups and downs, and a few flat spots, the broad trend has been upwards, especially if we neglect the sharp return to the slow upward trend following a brief late 2000’s boom associated with the 2009 stimulus package.

Very little of the housing stimulus was vouchers. The largest component of that stimulus program was public housing modernization. Plenty of existing public housing could use some modernization, but a much more effective stimulus could have been obtained had these additional funds been allocated to vouchers, as argued by Davis Malpezzi and Ortalo-Magné, Foote, Fuhrer, Mauskopf and Willen, and by Olsen.

One could debate the need for more funding, and one could certainly argue for some important structural changes in the design of housing choice vouchers (see below; and Fischer and Sard). Nevertheless, wherever we come down on these issues, Green and Malpezzi, among others, argue that low-income housing subsidies have broadly increased over the last several decades. During this period the mix has slowly become, on the margin, more efficient and more equitable as we moved from public housing and other supply-side programs to a greater emphasis on vouchers. We have also stated in the past that when housing choice voucher budget authority comes due, it’s been routinely rolled over, with modest increases over time. But as of this writing, that optimism may no longer be justified.

To see this, examine the red bars in Exhibit 1, which incorporate OMB’s current proposal for HUD spending on low-income housing. These comprise OMB estimates for 2017 (FY completed, but not yet fully reported) as well as the Administration’s plans for spending for 2018 to 2022. The Administration proposes to cut HUD’s nominal outlays from $49 billion in 2017 to $42 billion in 2022. Assuming inflation of 2 percent going forward, a little higher than recent rates but the Fed’s target, and real outlays fall to $38 billion.

Despite the growth in HUD subsidies over time, as we have remarked in the previous blog posts, such subsidies are received by only about a quarter of eligible households, with about a quarter of low-income households paying half or more of their income on housing (the two groups overlap but are not the same). This point will motivate some of our reform proposals, towards the end of this post.

Detail on Administration Proposals for Changes to Vouchers and Other Programs

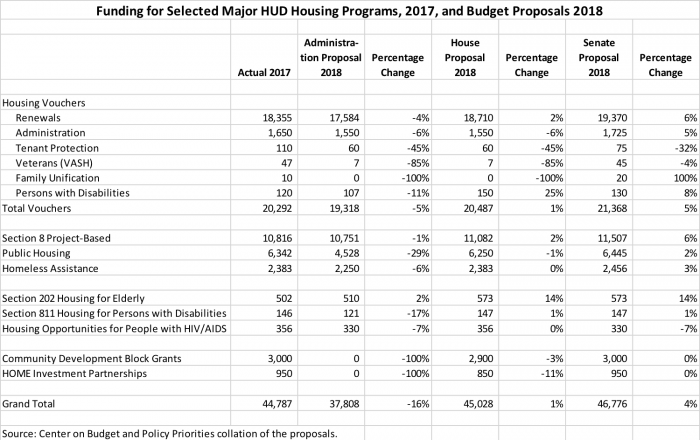

Exhibit 2 examines proposed budgetary changes in more detail. In the primary source on historical budget statistics, OMB did not break out the five-year forecasts of low-income housing spending by program. But recently the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities assembled first-year proposals by major program from the Administration, and the relevant House and Senate committees. USDA and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit data are omitted, as are data for a number of smaller HUD programs.

Exhibit 2 presents nominal amounts, so that if we adjusted for inflation we might subtract a percent and a half or so from the 2018 numbers.

Overall, the Administration’s proposed budget cuts nominal spending on the main low-income housing subsidies by 16 percent in the first year; the House budget is flat with a nominal increase of 1 percent; and the Senate proposes a moderate increase of 4 percent.

The Administration proposes to cut vouchers by 5 percent in the first year; the House roughly stands pat; and the Senate would increase nominal voucher funding by 5 percent.

The Administration argues for very large cuts to public housing, about 29 percent in nominal terms, while the House and Senate are roughly constant. The Administration and Congress all keep Section 8 Project-based programs fairly flat. Section 202 Housing for the Elderly is also held roughly constant in the Administration proposal but increased by 14 percent in both the House and the Senate; elderly people vote.

The Administration also penciled in a 17 percent cut in Section 811 Housing for Persons with Disabilities, which remains at previous levels in the Congress. Housing Opportunities for People with HIV/AIDS takes a significant 7 percent cut in the Administration and Senate proposals, but is held harmless in the House. Both Community Development Block Grants and the HOME Investment Partnerships are zeroed out by the Administration’s proposal; there are cuts in the House but the programs survive, and in the Senate the programs are held harmless.

Some of the Administration’s Proposed Changes in Housing Choice Vouchers

The Administration proposes adding new work requirements to housing assistance as well as to a number of other social programs. Whatever their final form, they may impose significant administrative costs but are unlikely to change labor-force participation or incomes very much. As we’ve seen in previous posts, a little over half of voucher recipients are elderly or disabled. A majority of those remaining have children, and the majority of non-disabled non-elderly already work.

As it happens, HUD has already been carrying out an experiment, Moving to Work, first in Dallas and then in nine additional housing markets (see Levy, Edwards and Singleton). Only one experiment, in Charlotte, has had a rigorous evaluation (Rohe, Webb and Frescoln). These have had, as Levy, Edmonds and Singleton note, “modest effects on employment and little impact on incomes.”

There are number of changes to income limits. Some changes will restrict eligibility. For example, medical expenses are still deductible from gross income before considering whether one hits the Very Low-Income or Extremely Low-Income thresholds we discussed in previous posts, but now only the portion over 10 percent of income will count as a deduction. If assets exceed $100,000, households are ineligible. Incomes of low-income households are often highly volatile, and once in a unit rents can change but households need to exceed thresholds for some time before they need to give up some subsidies. New rules that terminate housing assistance once income spikes to 220 percent of median have been put in place.

Some changes loosen eligibility. For example, the elderly and disabled deduction increases from $400 to $525. Certain veterans pension benefits are also excluded from the income calculation. There is also an increased threshold for when one must include imputed rent from assets; if a household’s assets are less than $50,000 this calculation is not carried out.

The Administration proposals would also raise rents; here we rely almost verbatim on Fischer Sard and Mazzara’s summary of some of the changes:

- Require state and local housing agencies and private owners of subsidized housing to raise rents from 30 percent of a low-income family’s income to 35 percent, and to eliminate certain deductions from these calculations for factors that reduce a household’s ability to pay rent, such as high medical or child-related expenses;

- Eliminate assistance for utility bills;

- Charge the lowest-income families minimum rents of $50 a month even if this exceeds 30 percent (or 35 percent) of their income;

- Let HUD make virtually any change to the rent rules for the housing voucher program, including imposing unlimited rent increases; and

- Cut payments for “enhanced vouchers” that protect residents from displacement in buildings that previously received other types of federal subsidies; and

- Eliminate payment increases in certain programs for rising operating costs or market rents.

Two of the proposals above are inconsistent. Raising voucher recipients’ required rent contribution from 30 percent to 35 percent will reduce work incentives, just as other proposals attempt to increase labor-force participation. Once employee contributions to Social Security and Medicare are factored in, this means that a housing subsidy recipient faces an effective tax rate of 43 percent of their income (assuming they pay no Federal or state income taxes). A minimum wage earner would thus take home about $4.15 per hour.

Another Trump administration proposal is a suspension of the required use of the so-called Small Area Fair Market Rents (“SAFMRS”) in 23 large metropolitan areas. Fair Market Rents (“FMRs”) are the benchmark against which housing choice voucher payments are calculated. Loosely, Fair Market Rents are usually close to the 40th percentile of market rents for units of standard quality within a defined geography. Historically, these were first calculated for the overall metropolitan area level, which often comprises several counties. But market rents vary a lot within metropolitan areas and circa 2000 most Public Housing Authorities began to calculate a county level FMR. Now FMR’s can vary within New York between Manhattan and Staten Island, to give one example.

SAFMRs take this logic further and are calculated by ZIP code. No such rough categorization of a market area will ever be perfect, but ZIP-code level SAFMRs will better reflect actual rents, giving recipients more choice in higher cost locations. Their use can also reduce excess payments in lower cost areas. Research shows that in at least one test case, Charlotte, SAFMRs reduced the overall cost of vouchers. One case study does not prove that such a fiscal gain would be replicated in all or even most metropolitan areas, but this shows promise for further research.

Under the Administration’s proposal, HUD would still permit voluntary adoption of Small-Area FMR’s, but there is a serious roadblock, namely the balkanization of Public Housing Authorities in many metropolitan areas. There are 382 metropolitan areas, but about 3400 PHAs; PHAs are responsible for the administration of most housing vouchers as well as public housing. This makes the necessary coordination difficult. So while some such as Fisher argue for the reinstatement of mandatory SAFMRs, it may be almost as effective, and generate other administrative efficiencies, if PHAs were consolidated, perhaps in line with proposals by Turner and Katz, for example.

Housing programs, like other government programs, are of course subject to sequestration rules. These are described briefly in the Appendix at the end of this post. In 2017 the Congressional Budget Office pointed out that sequestration would not be required in that year. It’s not clear what will happen in 2018; sequestration caps are lowered slightly, about 1 percent. More to the point, the recently passed Tax Cut and Jobs Act is a wildcard. It’s quite likely that the large budget deficits associated with that Act will trigger sequestration in housing and many other programs. Sequestration is not exactly a housing program issue per se, but it has not proven very effective in its goal of incentivizing legislators to be prudent budgeters (Hu and Zarasaga).

Some Additional Proposals for Improving Housing Subsidies, Including Vouchers

The most efficient and (potentially) most equitable approach to subsidizing housing is a housing allowance like Housing Choice Vouchers, as we have argued over several posts. But the program has room for improvement. In the previous section we considered several of the Administration’s proposals for change, including cuts in future funding that are perhaps the most notable area, but also some other proposals in areas such as measuring household incomes, and setting Fair Market Rents.

Other reforms can and should be considered. One set of reforms has to do with housing standards and inspections. HUD’s housing standards are moderately strict and limit tradeoffs. For example, a household might accept a unit with less ambient light (window/area ratio) if it is very well located relative to job and school. Simplifying standards and adopting a scoring system that facilitates more such tradeoffs could simplify the program and lower administrative costs, as well as improve recipient’s welfare.

We have discussed mainly vouchers, and in passing some other housing programs. HUD also provides block grants to local governments, which they can use for an array of purposes. The largest of these, the Community Development Block Grant (“CDBG”) program has been “zeroed out” in the Administration’s budget proposal, but it may survive given Congressional political support. Many local governments use some of their block grant money on housing, usually small-scale supply-side efforts. If CDBG and other block grant programs survive, efficiency and equity can both be served provided these local governments focus their block grant programs on vouchers too.

Although most low-income Americans rent, there are low-income homeowners as well as low-income renters. Tax subsidies (mortgage interest and property tax deductions) rarely benefit these households because the tax code only makes these subsidies relevant to households with a larger mortgage and/or tax bill than poor households usually incur. The changes in the Tax Cut and Jobs Act will cut these subsidies considerably, and focus them even more on what we might characterize as upper-middle income households. Green and Vandell, among others, have argued for changing the deductions to tax credits, re-designed in a way to reach down the income distribution to more potential first-time homebuyers of moderate income. HUD has a small homeownership voucher program for first-time homebuyers. The homeowner program operates at PHA discretion; most do not.

Recall that these HUD programs altogether assist about 4.7 million households, just under 10 million people. Depending on how we measure eligibility, these subsidies reach between ¼ and ⅓ of the 15 to 20 million households that are eligible, a major violation of horizontal equity. As others have noted, suppose that households eligible for, say, SNAP (food stamps) or the mortgage interest deduction, had their names placed in a lottery, where a third or a quarter of those eligible were randomly chosen to receive food stamps or the deduction, and the rest were out of luck. Most Americans would hardly think such a program was well-designed, many would think it fundamentally unfair.

One possible reform to solve this problem would be to revamp vouchers as an entitlement. Whether or not we all support such an idea, we can probably agree that low-income housing subsidy budgets are not likely to triple in the foreseeable future. There is another alternative. Olsen (2010) has argued for restructuring smaller, simpler vouchers as an entitlement, and has simulated likely household responses.

Stabilizing voucher funding is another useful reform proposal. Budget authority for vouchers lasts 5 years; i.e., every five years the money for existing vouchers must be re-appropriated. Historically this was done routinely, but in the current political climate, renewals are not as certain. In 2013, Congressional sequestration of the Federal budget required 73,000 housing vouchers cut. Congress did restore some funding, but the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reported that less than half the losses were to be restored.

Vouchers work best when there is an adequate stock of existing rental housing. But Olsen (2010) and others show that while higher vacancy rates help, vouchers are still more effective than public rental housing in tight markets, and that vouchers do improve housing quality on the margin. Vouchers can be combined with limited supply-side programs, e.g. for special needs populations, such as some variation of the Section 811 and Section 202 programs.

Collateral actions increase voucher effectiveness and housing conditions of low-income households. Improving supply responsiveness improves the operation of voucher programs. Improve the effectiveness of land use and development regulation; use regulatory cost-benefit as a guide to address environmental, neighborhood, other externalities without imposing unnecessary costs. Review regulatory treatment for landlords to ensure even-handedness with other investors. Are the financial and tax playing fields level between landlords and homeowners, between landlords and other investors? Watch this space for future posts!

Final Comments

Efficient programs are those that return the greatest benefit compared to costs. In our two previous posts, [post 1], [post 2] we presented a variety of evidence that vouchers were generally a more efficient use of scarce taxpayer dollars than public housing or other supply-side housing programs.

In the second of those posts, we also discussed how we might think about equity or distributional issues, which can be a little more difficult to parse than efficiency issues, because value judgments play a larger role. The second post explained the difference between horizontal equity – (the equal treatment of equals, e.g. all people of a certain income level) and vertical equity (how we treat “unequals,” e.g. rich versus poor). While both involve some value judgment, horizontal equity is probably easier to agree upon, at least in principle; after all, “equal protection of the laws” is famously enshrined in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In the previous posts, as in this one, we argue that Federal low-income housing programs in general, and housing vouchers in particular, violate the principle of horizontal equity by providing assistance to only a quarter or so of those eligible and/or “in need.”

If the Administration and Congress, and for that matter other levels of government, wanted to improve the efficiency and fairness of low-income housing subsidies, we would continue to move housing subsidies away from supply-side programs like public housing and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, and towards vouchers. As Professor Edgar Olsen has argued cogently in a series of papers and in a recent op-ed, by re-designing the voucher program around shallower subsidies to a wider range of recipients, we could serve many more poor households without increasing public spending. (Be sure to read the comments section when reading Olsen’s op-ed, where he has provided careful responses to several questions about his proposals.) Unfortunately, the current Administration proposals cut overall spending, while at the same time rents and low-income populations are rising. The proposals would shrink the subsidies to many recipients, but in a way that reduces rather than increases the incentive to work. By cutting overall funding and avoiding evidence-based redesign we give up an opportunity to improve the horizontal as well as the vertical equity and efficiency of the system.

Appendix: A Glossary of Selected Federal Budget Terms

This section provides an informal glossary of the jargon you need in order to understand elements of the Federal budget. I’ve simplified these descriptions and neglected many exceptions and clarifications. See GAO, “A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process” for more details and more precision. (That glossary is 182 pages long, so you know we’ve given up some!)

Mandatory spending: Congress defines eligibility and payment rules upfront but then implicitly authorizes whatever spending is required to meet the ensuing demand. Once enacted, mandatory programs do not require appropriations.

Discretionary spending: not mandatory; requires annual appropriations (see below). Defense programs as well as many domestic programs are “discretionary,” even though they may be very necessary. Discretionary programs are about ⅓ of Federal spending.

Entitlements: programs open to any qualifying individuals or other entities; see mandatory spending. “Mandatory” and “entitlement” are often loosely treated as synonyms; but interest on the debt, categorized as “mandatory,” is not usually labeled as an entitlement.

Budget authority: gives an agency legal authority to enter into a financial commitment for spending, now or in the future. There are three types of budget authority: appropriations, borrowing authority, and contract authority.

Appropriations: enables an agency or department to legally make spending commitments and actually spend money. The majority programs subject to appropriations must have their funding renewed annually, but among the exceptions are housing programs. Supply-side housing programs (e.g. public housing) can have up to 20 years of budget authority. Housing Choice Vouchers usually have 5-year budget authority, which can be renewed.

Congress is not legally bound by multi-year budget authority; while in the past housing BA has been renewed, Congress can fail to renew, and/or reduce the appropriation on its own, or by approving a “recission” proposed by the President.

Borrowing authority permits an agency to borrow, usually from the Treasury, and then to spend against the amounts borrowed.

Contract authority, less common than the other two, permits an agency to incur obligations first and then to seek an appropriation or collect funds sufficient to pay for the spending.

Sequestration is the cancellation of budgetary resources provided by discretionary appropriations or direct spending law.

PAYGO or Pay-as-You-Go requires legislation that either reduces revenues or increases mandatory spending above a defined baseline to be offset by equal revenue increases or mandatory spending reductions. If a full offset is not enacted, then a PAYGO sequester is triggered. There have been several versions of PAYGO over recent decades; the current version is based on a 2010 law.

In addition to PAYGO, the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) imposed additional caps on discretionary appropriations for both defense and non-defense programs annually through 2021. Appropriations above the cap in either category trigger sequestration in that category to reduce funding to the cap.

The BCA also requires additional sequestration aimed at reducing projected deficits. However, Congress can and has written exceptions to the sequestration rules as they have found politically convenient.

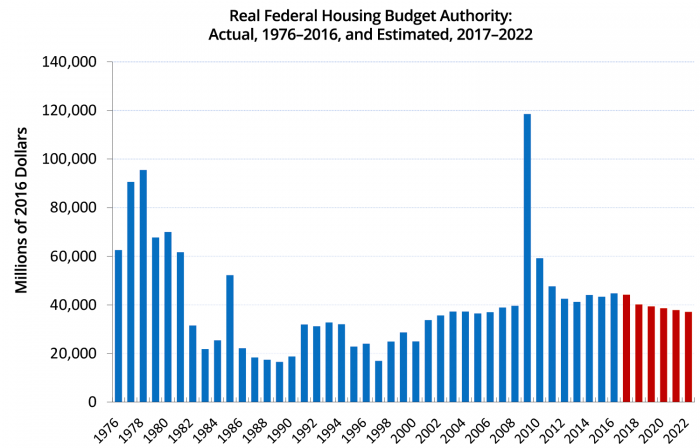

Appendix 2: Budget Authority Compared to Outlays

Exhibit 1, above, might surprise some readers, since so many stories in the popular press, and some articles by advocates (Hartman 1986), have given the mistaken impression that budgets for low-income housing have already been dramatically cut, starting with the Reagan administration in the 1980s. This is partly due to the narrow focus of some observers on supply-side projects alone – if I can’t put a sign with a politician’s name on it, nothing’s been accomplished. Cutting a check is a less visible action even if it’s more effective. And HUD under Reagan famously had a series of scandals that tarnished the agency (Moe 1991).

But another reason is a basic misunderstanding of federal budget jargon. A glossary of some of the terms can be found at the end of this post.

The most common source of confusion on this issue is the difference between Federal budget authority and outlays. Budget authority for housing (Exhibit 2) fell from a high of roughly $90 billion (2016 dollars) in the late 1970s to the current level of around $40 billion per year. During the late 1980s such budget authority fell under $20 billion per annum.

But budget authority for housing is a multiyear promise to spend money in the future. Budget authority figures are affected by several quirks in budgetary procedures, the most important of which is that different programs require budget authority of varying duration. Programs such as public housing require the U.S. Congress to authorize expenditures for as many as 20 years into the future, while vouchers and other demand-side programs require only 5-year budget authority. To date, as previously authorized subsidies have come due, Congress and the President have cooperated in rolling them over, but recently this automatic rollover has been challenged.

So a much better measure of actual spending on housing is outlays. We present Exhibit 2 for comparison and to explain the source of budget confusion; for our purposes, to see how much we spend every year, Exhibit 1 is preferred.

Sources and Further Reading

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Average Housing Voucher Costs Fell at Agencies Using Small-Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs).” 2017.

Chan, James L. “Government Budget and Accounting Reforms in the United States.” OECD Journal on Budgeting 2, no. Supplement 1 (2002): 187-221.

Collinson, Robert, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Jens Ludwig. “Low-Income Housing Policy.” Economics of Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States 2 (2016): 59.

Davis, Morris A., Stephen Malpezzi and François Ortalo-Magné. “The Wisconsin Foreclosure and Unemployment Relief Plan (Wi-Fur).” James A. Graaskamp Center for Real Estate, http://www.bus.wisc.edu/realestate/wi-fur/.

Davis, Morris A, Jess Gregory, Daniel A Hartley, and Kegon Teng Kok Tan. “Neighborhood Choices, Neighborhood Effects and Housing Vouchers.” (2017).

Delisle, Elizabeth Cove. “Changes in Federal Housing Assistance for Low-Income Households.” Congressional Budget Office, 2017.

Ellen, Ingrid Gould. “What Do We Know About Housing Choice Vouchers?”: NYU Furman Center, 2017.

Eriksen, Michael D, and Amanda Ross. “Housing Vouchers and the Price of Rental Housing.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7, no. 3 (2015): 154-76.

Falk, Gene, Maggie McCarty, and Randy Alison Aussenberg. “Work Requirements, Time Limits, and Work Incentives in TANF, SNAP, and Housing Assistance.” Congressional Research Service (2014).

Finegold, Kenneth. “Block Grants: Historical Overview and Lessons Learned.” (2004).

Fischer, Will. “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains among Children.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2014).

———. “Work Requirements Would Undercut Effectiveness of Rental Assistance Programs.” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www. cbpp. org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-14-16hous. pdf (2016).

Fischer, Will, Barbara Sard, and Alicia Mazzara. “Trump Budget’s Housing Proposals Would Raise Rents on Struggling Families, Seniors, and People with Disabilities.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017.

Foote, Chris, Jeff Fuhrer, Eileen Mauskopf, and Paul Willen. “A Proposal to Help Distressed Homeowners: A Government Payment-Sharing Plan.” http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/ppb/2009/ppb091.htm.

Freeman, Lance. “The Impact of Source of Income Laws on Voucher Utilization.” Housing Policy Debate 22, no. 2 (2012): 297-318.

Green, Richard K., and Stephen Malpezzi. A Primer on U.S. Housing Markets and Housing Policy. American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association Monograph Series. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 2003.

Hartman, Chester. “Housing Policies under the Reagan Administration.” Critical perspectives on housing (1986): 362-76.

Isaacs, Julia B, Cary Lou, and Ashley Hong. “How Would Spending on Children Be Affected by the Proposed 2018 Budget?”. (2017).

Katz, Bruce J, and Margery Austin Turner. “Who Should Run the Housing Voucher Program? A Reform Proposal.” (2001).

Leventhal, Tama, and Sandra Newman. “Housing and Child Development.” Children and Youth Services Review 32, no. 9 (2010): 1165-74.

Levy, Diane K, Leiha Edmonds, and Jasmine Simington. “Work Requirements in Public Housing Authorities.” (2018).

Lubell, Jeffrey M. “Recent Improvements to the Section 8 Tenant-Based Program.” Cityscape (2001): 85-88.

Martin, Carmel. “Fixing Sequestration and Improving the Budget Process.” Center for American Progress (2015).

Mazzara, Alicia, Barbara Sard, and Douglas Rice. “Rental Assistance to Families with Children at Lowest Point in Decade.” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2016).

Moe, Ronald C. “The HUD Scandal and the Case for an Office of Federal Management.” Public Administration Review (1991): 298-307.

Newman, Sandra, and C Scott Holupka. “The Effects of Assisted Housing on Child Well‐Being.” American journal of community psychology 60, no. 1-2 (2017): 66-78.

Office of Management of Budget. “Historical Tables.” Washington, DC, 2017.

U.S. Congressional Budget Office. The Cost-Effectiveness of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Compared with Housing Vouchers. Washington, D.C.1992.

Olsen, Edgar O. “Getting More from Low-Income Housing Assistance.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project, 2008.

Rice, Douglas, and Barbara Sard. “The Effects of the Federal Budget Squeeze on Low-Income Housing Assistance.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, mimeo, 2007.

Rohe, William M, Michael D Webb, and Kirstin P Frescoln. “Work Requirements in Public Housing: Impacts on Tenant Employment and Evictions.” Housing Policy Debate 26, no. 6 (2016): 909-27.

Sard, Barbara. “Housing Vouchers Should Be a Major Component of Future Housing Policy for the Lowest Income Families.” Cityscape 5, no. 2 (2001): 89-110.

Sard, Barbara, and Douglas Rice. “Realizing the Housing Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Move to Better Neighborhoods.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated January 12 (2016).

Scally, Corianne Payton, Samantha Batko, Susan J Popkin, and Nicole DuBois. “The Case for More, Not Less.” Urban Institute, 2017.

Shapiro, Isaac, RIchard Kogan, and Chloe Cho. “House GOP Budget Cuts Programs Aiding Low- and Moderate-Income People by $2.9 Trillion over Decade.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017.

Theodos, Brett, Christina Plerhoples Stacy, and Helen Ho. “Taking Stock of the Community Development Block Grant.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute (2017).

Turner, Margery Austin, and Susan J. Popkin. “Why Housing Choice and Mobility Matter.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2010.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “Budget Outlays by Program.” Washington, DC, 2017.

Waxman, Elaine, and Linda Giannarelli. “The Impact of Proposed 2018 Changes to Key Safety Net Programs on Family Resources.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute 2100 (2017).